The Struggle for Time:

History, and Memory in Belarusian Art

By Aliaxey Talstou

Translated by Jim Dingley

The struggle over public memory has galvanized Belarusian artists in recent years. In a society ruled by an authoritarian government intent on obfuscating historical truth, it is left to independent artists, cultural activists, and intellectuals to reclaim the past.

To appreciate this turn in Belarusian art, one must first understand our recent history. Aleksandr Lukashenko came to power in 1994 in the aftermath of the Soviet Union’s collapse. At a time of great uncertainty and hardship, he promised a return to the economic stability of Soviet times and initially won voters’ support. Once elected president, he allied the country closely to Russia and later, in 2004, had the constitution altered to allow the president to stand for election an unlimited number of times. This, taken together with the president’s total control of the Electoral Committee, turned elections into something akin to a ritual, rather than an opportunity for change.

For the past twenty-three years, then, Belarus has been mired in the past, in the stability of an empire that has been artificially re-created for internal use. This artificiality bears all the hallmarks of a façade behind which the authoritarian leader and his entourage lead their perfectly natural, modern lives. In contrast to other countries of the region where the market reforms of the nineties led to the creation of an oligarchy, in Belarus it is the state itself which has been ‘privatized’. The old Soviet colonial myth of the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic has been updated to suit modern times.

Opposition parties remain unpopular, in part because they have such limited means with which to communicate their message to the public. It is also the case that the opposition is associated with the right-wing nationalism that sprang from the dissident national revival of the 1980s. Thus, the opposition remains largely defined by its anti-colonial, nationalist passions. Periodically, the resistance to Lukashenko has gathered demonstrations in the streets of Minsk and other towns, but these signs of dissent have been swiftly stifled. Most recently, an outbreak of protests in the spring of 2017 came to an end after security forces violently arrested and jailed numerous protesters and opposition leaders. Given the inefficacy of the opposition to Lukashenko, the cultural situation in Belarus is to a large extent determined by the Soviet conservatism of the authorities and the still unresolved question of national identity.

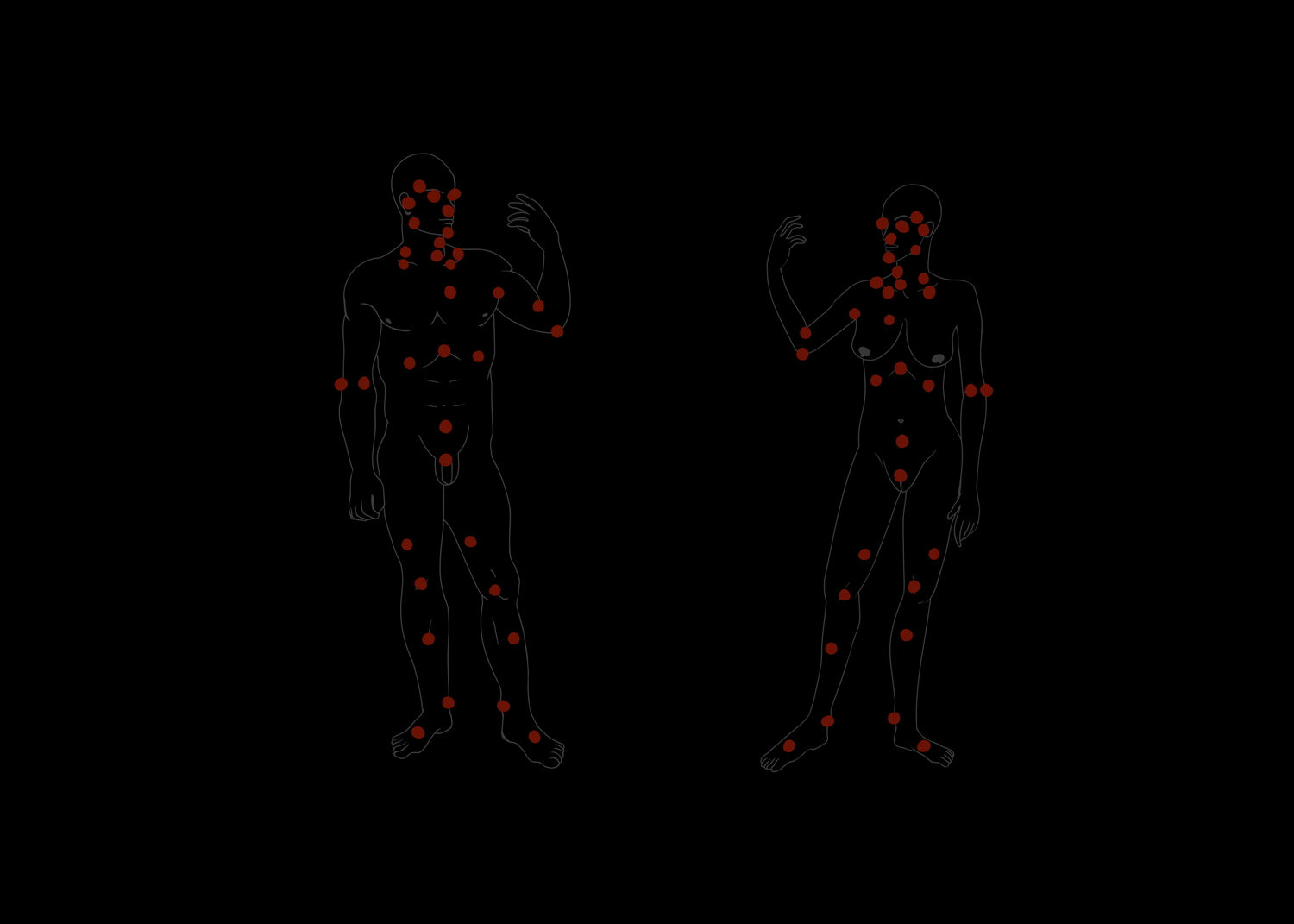

Since 2010, contemporary art in Belarus has subtly sought to counter that conservatism, by reinvigorating historical memory and reclaiming lost time. A case in point is Maxim Sarychau’s February 2017 exhibition, Blind Spot, in the gallery of the CECH, an educational and cultural center in Minsk. The room is plunged into semi-darkness. Varying levels of light shine upon images and objects on display. The works emerge from the uncertainty of darkness; they do not reveal themselves in their entirety. In the background, we see large-scale graphics taken from medical textbooks. Silhouettes of bodies, arms, and heads are marked with red dots indicating the spots where the greatest pain will be caused when hit. Next to them is a huge depiction of the brain, similarly marked to show where fear is aroused.

Maxim Sarychau, Blind Spot, 2017. Graphics from a martial arts textbook depicting areas most susceptible to pain and injury on the human body. Image courtesy of the artist.

Elsewhere we encounter photographs. One shows us an anarchist with huge bruises on her shoulder. Who or what caused the bruises? The artist leaves the question unanswered, yet the implication is that government security forces are responsible. Next to this image is a photo of the Kurapaty Forest near Minsk, a site of mass shootings during the Stalinist repressions of the 1930s. A row of red crosses erected by right-wing, nationalist activists can be seen through pine branches. There is also a staged shot on the same subject: a person kneeling by a newly dug grave in the forest. An archival, black-and-white photograph depicts a group of anti-Soviet partisans in informal poses—an image obviously taken by the partisans as a souvenir. Above each of the fighters, however, is a number written by an investigator of the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, indicating the Soviet regime’s (successful) efforts to wipe out post-war resistance. By placing such archival images from the Soviet past alongside those depicting contemporary political struggles, Sarychau draws a stark parallel between Soviet history and the present.

Another level of the exhibition features objects selected for their historical and political potency. A loaf of black bread divided into six equal pieces refers to a prison cell; the portions are exactly the amount of bread allocated to inmates in Belarusian prisons. A lump of paving stone speaks of street protests, as does a soldier’s truncheon sawn in half. Again, the juxtaposition of these objects compels the viewer to connect the repressions of the past to those of the present. By combining objects and images in this fashion, Sarychau creates a unique picture of political violence and human rights.

Maxim Sarychau, Blind Spot, 2016. Photograph of Alena Dubovik, 30 years old, beaten by police officers during transportation to the police station. Later in the spring 2017 mass protests, she was was arrested for twelve days and went on a hunger strike. Image courtesy of the artist.

Artists like Sarychau are eager to highlight political conditions as they truly are, in contrast to the fictions peddled by Belarus’s official mass media. Such criticism teeters on the very edge of what is permitted. Authorities do not harass these independent artists only because their exhibitions attract a comparatively small number of people. Yet projects like Blind Spot do more than provide an alternative vision of the present; they call attention to the past through historical reference and thus offer an alternative reading of history. They do not, however, suggest ways of solving political problems. This approach to history in artistic discourse implies that people have yet to come to terms with the trauma caused by the authoritarian Soviet system. In all likelihood, such a reckoning will not be possible while an ideological model that denies this trauma holds sway.

Maxim Sarychau, Blind Spot, 2017. A photo of the Kurapaty Forest near Minsk, a site of mass shootings during the Stalinist repressions of the 1930s. Courtesy of the artist.

Another exhibition in Minsk last year ventured into the realm of public memory. Aptly titled The Past is Still Not Over, the Future has Already Not Come, this show by artist Anton Sarokin, held in Gallery Ў last summer, drew upon post-independence video and audio recordings to create nostalgic montages. The work gives shape to different kinds of memories, including those that are unsupported by the ruling ideology, and are gradually being swallowed up by media noise. In the video installation Probably Absent User, computer monitors display screen savers with scenes from salient historical developments of recent years, such as the relighting of the Eternal Flame on Victory Square (after it had been extinguished by the weather). Similarly, Sirens, a work based on a MIDI controller, contains sounds recorded during street protests. Visitors to the gallery could produce sound patterns of their own from a bank of sixty-four audio samples. Such interaction creates a musical track that more than anything serves as a kind of flashback, a greeting from the recent past.

Other works of Sarokin reference the disaster at the Niamiha metro station in 1999, in which fifty-three people died in a stampede, the violent street protests following the falsification of the presidential election results of December 2010, the bombing of the Kastryčnickaja Square metro station in April 2011, and the trial of the two accused, who were sentenced to death.

It is precisely events such as these which will never be mentioned by the state; they are that part of the country’s history which can be preserved only through the efforts of society at large. Sarokin renders visible things that many people have already forgotten, or which are simply unknown to others because of their youth. In their notes on the exhibition the curators, Inha Lindarenka and Maria Yashchanka, employ the term ‘hauntology’ that Jacques Derrida coined to denote the simultaneous existent and non-existent status of ghosts. This is a fitting term to describe the images displayed in the exhibition.

Anton Sarokin, Probably Absent User, part of the gallery show The Past is Still Not Over, the Future has Already Not Come, 2017. Photograph of a computer monitor displaying a found footage screensaver to reflect on memories of the Belarusian past that have become lost in the noise of the present. Photograph courtesy of Victoryja Harytonava.

The aim of official policy in Belarus today is to preserve the legitimacy of existing power structures, as well as of the social order inherited from the Soviet past. To achieve these ends, the regime works to deny history and corrupt public memory. In response, the independent cultural community in Belarus has taken upon itself a task that is in direct opposition to the official line: a struggle not just for power, but for the possibility of achieving harmony with the modern world, for open access to new information, and against a conservatism that is closely linked to the performative rhetoric of Soviet tradition.

False political ritual was a widespread phenomenon in the Soviet Union. One could agree with and declare support for positions that had little connection with reality. Similarly, in Belarus today, it is perfectly possible to agree with what the president says about political pressure from the West and to make shopping trips to Lithuania and Poland. One can join the pro-regime Belarusian Republican Union of Youth while contemplating immigrating to western Europe. Of course, the greatest manifestation of performativity is to be found in elections. While everyone knows that elections at all levels are falsified, many people regard the physical act of voting as a duty. During local elections, many voters know nothing about the candidates before going to the polling station. Yet the authorities use every possible means of getting people out to the polls by striving to create the atmosphere of a public holiday, offering entertainment and cheap alcohol at polling stations.

Such performativity has long interested the artist Olia Sosnovskaya. Her complex body of work explores a variety of

themes, including the ritualistic nature of Soviet and post-Soviet festivities. One of her recent works—the choreographed performance, Not Yet, Not Yet, Again and Again—deals with several topics including work conditions, public protests, historical narratives, and collective memory. In June 2017 she and fellow performers presented the two-hour piece at the abandoned Il’ich Palace of Culture in the Ukrainian city of Dnipro.

This dilapidated structure, built in the constructivist style of the 1930s, once served as the cultural center for the workers of the largest factory in the city. The palace was an essential element of this site-specific work. Performers moved through the vast square in front of the palace, sitting and lying on the main stairs, walking through the arches. Improvisatory choreography reflected the architecture, though also correlated with personal memories about the palace and the performers’ experience of street protests. Readings referenced labor protests that had taken place in the city prior to the October Revolution, and much more recent protests, such as Occupy Wall Street, the Women’s March, and the Maidan in Kiev in 2014. The performance thus sought to integrate worker rebellions of the early twentieth century with the Soviet history of the structure and contemporary protest experience. Sosnovskaya thus compelled her audience to consider the relation between labor, protest, and the body as a political entity throughout history.

Olia Sosnovskaya, Not Yet, Not Yet, Again and Again, 2017. Photograph of Sosnovskaya performing improvisational choreography in the abandoned Il’ich Palace of Culture in Dnipro, Ukraine to memorialize the street protests and personal memories that occured within the space. Photograph courtesy of Vlad Lemm.

The Ukrainian location is key to appreciating the potency of the complex performance. Today the pro-western Ukrainian government is aggressively seeking to erase signs of the country’s Soviet past from cities and towns–by removing monuments and outlawing the use of communist symbols. By staging her performance at this abandoned Soviet relic, Sosnovskaya implicitly resists the effort to erase this part of history from public view. Performers were encouraged to share their personal experiences with the structure; one person recalled music classes at the palace when it was still functional; another revealed that his father had worked on a subway line nearby. In this way, the performance commemorated the personal dimension of the Soviet and post-Soviet eras, as they were lived.

Sosnovskaya’s work can be seen in opposition to the Ukrainian right-wing nationalist rhetoric, which backs the government’s policy of de-communization. Such a radical, uncritical rejection of history exaggerates the status of victimhood. On the one hand, the Soviet experience was traumatic for many; on the other hand, denying that history in such an aggressive, active manner does not seem natural either. Unfortunately, Belarusian right-wingers fully support the Ukrainian government’s approach.

Of course, contemporary art in Belarus is not restricted to the theme of historical memory, but this subject matter has become conspicuous for good reason. The theme manifests itself as a form of political confrontation, a dynamic that is characteristic of other countries in the region.

In the digital age, in which many of us turn to social networks for information, the urge to reinvigorate collective memory is of dire importance. In this post-truth era, memory is more tightly tied to information technologies and vulnerable to media influence than ever before. The process of storing memories has yielded to the algorithms of social networks, which are hardly designed to cultivate knowledge and understanding. Rather, they encourage an uncritical stance towards new information and simultaneously open the way more readily to the acceptance of propaganda.

This situation is by no means specific to the region; it is, however, understandable that the clash of historical narratives and different approaches to the history of eastern Europe in many ways determines the political agenda. A cultural model founded upon one particular reading of history becomes essentially a weapon in the political struggle. Memory and history thus become a kind of battlefield where these artists operate.

Unfortunately, manifestations of this theme can be seen as provincial. Without drawing parallels with European or global contexts, such artistic practices can lead to self isolation. Sometimes it is hard to share such art with audiences that are unfamiliar with local issues. Every exhibition, every artistic statement consumes the artists energy and time. Instead of representing themselves and Belarusian art internationally, our artists have often concentrated their efforts on local struggles.

This concentration on history also diverts attention away from other urgent problems of the day with which politically motivated art has to engage–ecology, artificial intelligence, and migration, to name a few. However, we can understand why it is that artists who frequently work with local materials cannot fail to touch upon history and memory. Until we are able to overcome the experience of the Soviet and immediate post-Soviet past, and until the geopolitical situation in the region stabilizes, history and memory will continue to be relevant themes for artists and curators.

Aliaxey Talstou is an artist, curator, and writer based in Minsk, Belarus, active at the scene of Belarusian contemporary art since 2009. Author of solo shows and participant of various group exhibitions, curator and co-curator of several shows in Belarus and Russia, such as Boundaries of the Other (gallery CECH, Minsk, 2016), Talking about Politics (DKDS, Moscow, 2016) and Fortress Europe. Eastern Bastion (KX gallery, Brest, 2016). Talstou works with the themes of politics and activism in art and culture as well as with issues of migration, xenophobia, and tolerance. Former art director of cultural and educational center CECH in Minsk.