FICTION

THE PERMANENT COLLECTION

Fiction By John Powers

Illustrations by Raven Reyes

They arrived early, before the doors opened. He got two coffees and a muffin from a vending cart. The muffin must have weighed half a pound. He couldn’t remember the last time he had an appetite.

“I just want you to think about it,” she said. “That’s all I’m asking.”

He sat beside her on the granite steps. A pigeon landed at their feet. The pale feathers at its neck shimmered green and grey like a patina of bronze.

“Look at this guy,” he said.

The pigeon hopped closer.

“He’s got us pegged as tourists.”

The bird tilted its head, impatient.

The man laughed. It amused him to be mistaken for an easy mark.

He remembered when this city wasn’t such a clean pleasant place. A tough spot to scratch out a living. Especially for pigeons, he figured. Scavengers never did well in a downturn.

“Don’t feed them. They’ll swarm,” said his wife.

“This guy? He knows how to keep a secret.”

He tossed a few crumbs. Soon a dozen birds were scrambling. He scattered the rest of his breakfast, morsel by morsel, failing to disperse the mob.

“Did you hear a single word I said?”

“Of course,” he told her. “Every syllable.”

“And?”

“And I’ll think about it.”

“Promise,” she said.

“Cross my heart and hope—” He made a tragic gesture.

“That’s not funny,” she said.

He smiled and took her hand. The sun cleared the rooftops across Fifth Avenue. He considered taking off his sportcoat.

“They’re opening up,” she said.

She stood and reached for her purse.

“Hurry,” she said. “There’s a line forming.”

The museum was dark and cool beyond the revolving doors. People pushed past him into the main lobby. He paused to wipe his forehead, falling a step or two behind his wife. Crossing the great marble hall he could feel himself descending below the banks of a strong and silent river, swept along in its currents, carried downstream through dark eddies of forgotten decades. He felt his mind drift, dropping below the surface. He blinked, twice, caught in an undertow that pulled him farther and farther from shore.

He muttered something and struggled to collect himself. His wife stopped ahead to consult a floorplan. When he had first begun experiencing these episodes, weeks ago, he had feared it was senility, some kind of early onset. His overwhelming instinct had been to hide it from everyone.

“We don’t need a map,” he told her. “I know where we’re going.”

“Maybe I want to see some things, too.”

“By all means,” he said.

They had some confusion at the admission desk. He didn’t understand why he needed to show his driver’s license. He thought the arrangement was pay-what-you-wish. A kind of gentleman’s agreement.

He assumed it had something to do with his age.

“We don’t qualify for the senior discount,” he clarified.

The clerk smiled at him. It was the kind of smile that takes practice. “General admission is twenty-five dollars unless you are a resident of New York,” he explained, “or a full-time student.”

“But what if . . . ”

He didn’t intend to start an argument. But what if you moved to the city, fell in love and got married, and then in a moment of weakness, your wife convinces you to move to South Orange—New Jersey, for chrissakes!—because she’s pregnant with your second child, and she’s tired of living in a fifth-floor walk-up and because her father is still alive and looking for somebody to take over his brokerage, but ever since the day you got off the bus from Lubbock, that very first moment in the city, you’ve always been a New Yorker. In your heart, right here. Shouldn’t that count for something?

The clerk repeated the price of admission.

“Unless you’re interested in becoming a member?” A brochure was opened as the clerk recited benefits and levels of largesse.

“Patron’s Circle,” he replied. “That sounds about right.”

He handed over a credit card. Signed for fifteen hundred dollars. That was the other version of pay what you wish, known as pat yourself on the back. They had other phrases for it in Essex County. His mother-in-law swore if anyone ever asks how much, it means they can’t afford it. He imagined her estate planner nodding in approval. Personally he never gave a piss about money. He would have paid anything, everything, for the feeling of being back where he belonged.

His wife was staring at him. “Another headache?”

“It’s nothing,” he said.

She searched his face. “You’re sure?”

“We’ll write it off as a donation.”

“You just seemed, sort of—”

“Tax deductible,” he said.

They climbed to the second floor, continued past the Old Masters and the museum store. He skipped the Monet and Van Gogh and all the galleries congested with tour groups. At the end of the next hallway was a sculpture by Dan Flavin, a fluorescent tube that appeared to be pointing in the right direction. But the passage was blocked by some kind of temporary wall, white panels on wheels. A dead end.

The last time he had been there, that corridor opened into a series of abstract expressionists. The American men’s all-star team from the 1950s. He recalled color fields by Clyfford Still that looked like massive scabs peeled from the skinned knees of the world.

He approached a museum guard.

“Did you move the entrance to contemporary art?”

“Picasso—if that’s what you’re looking for—is with Early 20th Century European Painting. Directly behind you down the ramp.”

“Who said anything about Picasso?”

The guard shrugged. “Lots of people.”

“Contemporary art,” he repeated. “Last fifty years.”

“Those galleries on this level are closed for re-hanging. A selection of that work has been moved to the mezzanine. Take the elevator to your right.”

The show upstairs was cramped and mostly a disappointment. Predictable chart-toppers of modernism. He moved briskly through the usual suspects, before finding a few favorites worth lingering over, Motherwell, Diebenkorn, Dove…

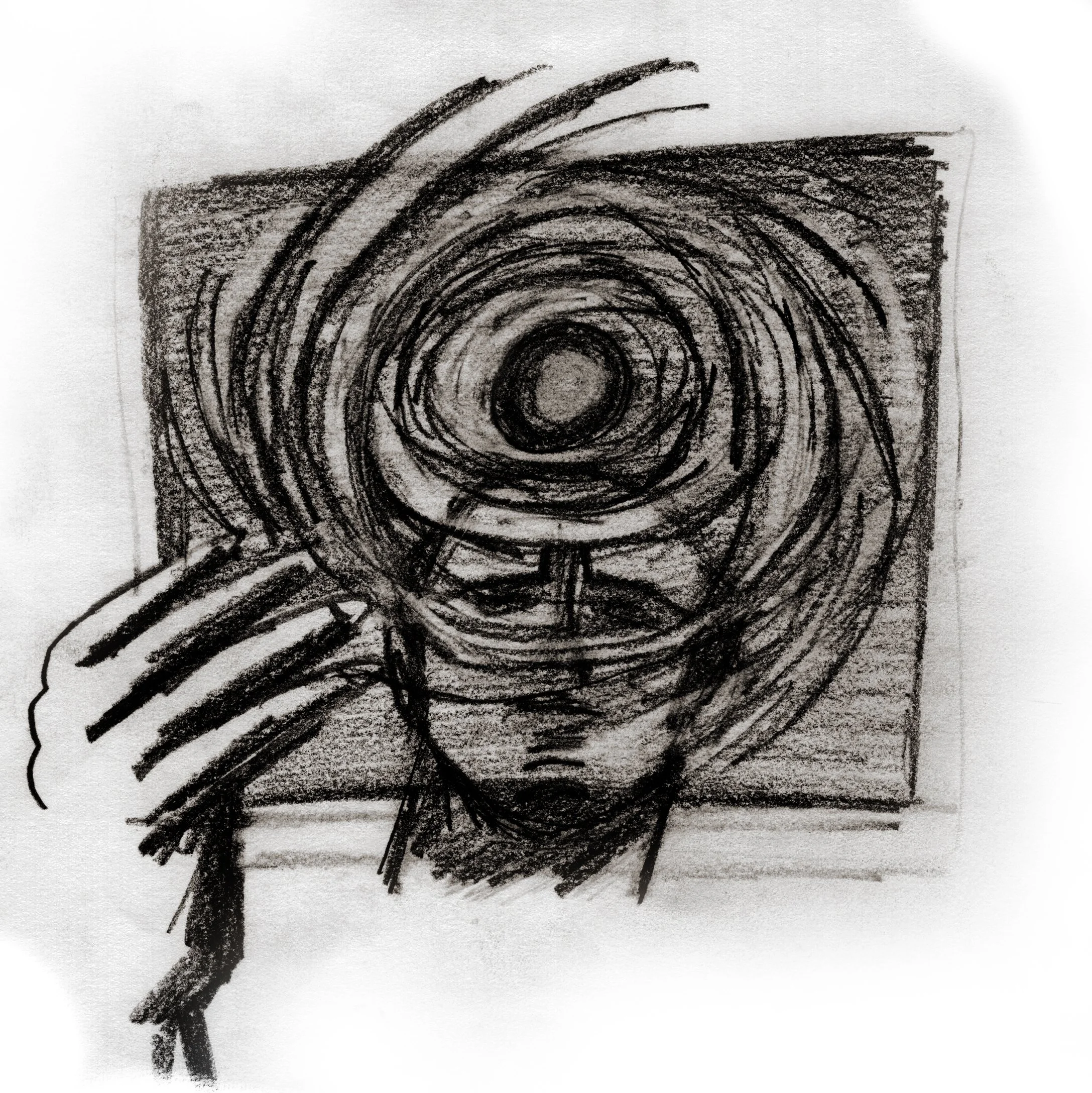

He found himself drawn to a small piece on the far wall. It was a shallow box that glowed like a guttering candle. It seemed familiar, somehow. Layers of tissue-thin paper, cut like children’s snowflakes, cascaded into shadows behind a cover of shattered glass. It looked like something lovely and delicate had been smashed with a fist, followed by a halfhearted attempt to repair the damage.

Untitled #359.

He read the artist’s name on the wall.

Evelyn Grossman (1954 - 1989).

Wood box, electric light, vellum and glass.

“I know her,” he said.

“Hmm. You like this one?”

“The woman who made it,” he said. “The artist. I know—I knew her.”

“It’s very pretty,” his wife said.

She was right. There was no denying it. It didn’t matter how many times he’d been told pretty should only be used as an epithet. He glanced again at the name on the wall. He saw her face, still young, framed by dark curls. Evie Grossman.

“We were—friends.”

His wife read the label.

“Oh,” she said. “She was so young.”

The piece had been made the year before her death and it was pretty and it was serious and it seemed to open from the inside like a fountain of sorrows.

“She made it into the Metropolitan,” he said. “That’s not for nothing.”

###

Evie Grossman had spent her seventeenth summer in a locked ward upstate. A private room with a view of the Catskills. Scissors were forbidden for obvious reasons. Pens and pencils were only available in controlled settings. They encouraged drawing and painting in group sessions, but she sensed whatever she put down on paper would attract too much scrutiny, probably extend her stay by another thirty days. So she began assembling model airplanes. Tommies, Spitfires, Hellcats. They came in boxes with tubes of glue and a thousand pieces of grey plastic. She found the first kit in the craft room. Her grandfather brought the rest, one or two a week. He helped her hang them above her hospital bed with dental floss.

That was the summer, she told him, she made up her mind to become an artist. She saw it as a matter of life and death. When she finally returned home, she smashed the model planes into piles of broken parts, and reassembled them, piece by piece, until they emerged as something else, something scarred and stripped of secrets, their true and hidden selves.

He had lived with her for five, six months.

It ended in a fight. Everything ended in a fight in those days.

He’d met his wife a year later. His friends swore it wouldn’t last. He’d shown a taste for high drama, women who broke things and wept in public. What was he going to do with some graduate assistant from Teachers College? Who was he trying to fool?

They met at a party near Union Square. She felt out of place, self-conscious in pumps and a worsted skirt. He wore paint-specked boots and his cleanest white t-shirt. He stood in the center of the room, smoking. He was having an argument.

“An artist’s artist?” he said. “If that’s not the most backhanded compliment...”

The other man, his friend, gestured with his drink.

“They love you at the League. You can always teach.”

“Always? What an awful thing to say.”

“Listen to me, you don’t need ideology. Nobody cares about color theory. People will buy anything in this market as long as you make it accessible. Look at Schnabel or Kenny Scharf. You just gotta loosen up a little.”

“Schnabel? Are you serious?”

“I’m telling you,” said his friend. “Try dumbing it down.”

Her cousin knew the hostess, a former classmate, who made the introduction. He offered her a cigarette, which she refused. He lit one for himself. Somebody had cleared a dance floor, but nobody danced. All the chairs and furniture had been dragged to the wall.

“Looks like seating for a firing squad,” she observed.

“You’ll be safe with me,” he said.

“I doubt that entirely.”

He laughed and glanced at the floor.

“You’re probably the first one they’d shoot,” she added.

“Me?” he said. “I’m no revolutionary.”

“You’re the tallest, though. They might mistake you for a leader.”

The others moved around them at a respectful distance. He had a reputation for fitful brilliance, her cousin told her, and being stubborn as hell. If that was meant as a warning it went unheeded. She, herself, was practical. Pragmatic, was the word. One foot in front of the other. She made plans, she pursued them. He was exactly the sort of person she’d intended to meet when moving to the city.

“Want to get some fresh air?” she suggested.

His friends didn’t believe him until it was done. The wedding, two kids, the moving van. It was only on rare occasions that he wondered how it had worked out at all.

They had lunch in a cafe near the sculpture garden. She wanted to talk about the retirement dinner. He pretended to eat a turkey sandwich while staring out at the sculpture of poor Count Ugolino, perpetually starving with his children at his knees.

“Josh and Beth are flying in,” she said.

“The boys don’t need to come.”

“Of course they do,” she said. “Jeremy asked if he could bring someone.”

“Okay, fine.”

“His name is Rashawn. We haven’t met him.”

“I’m sure it’s fine.”

“We should finalize the list. It’s only a couple weekends away. We still need to send out invites.” She took a small notepad and a pen from her purse. She pressed for names, titles, spouses.

“We’re up to a dozen guests,” she said.

“That’s enough,” he said.

“The room seats thirty.”

He appreciated her effort but was almost incapable of participating in the conversation. He saw no point in coercing every coworker to raise a glass in his honor. He doubted he would ever see them again. He had once been close with her father, who had built the business, but that was a long time ago.

On the day she turned twenty-five, she introduced them over brunch at the Russian Tea Room. Her father drove up from Metuchen. She had told him what she wanted for her birthday, but he seemed confused by the nature of the request.

“You want me to buy a painting?” Her father’s voice carried across the crowded room. “From your boyfriend?”

“From the gallery,” she explained. “Consider it an investment.”

She handed him the price list. She’d folded it into her purse on opening night, already planning ahead.

“Two grand?” Her father frowned. “Pretty steep for some starving artist.”

“When he’s famous, you’ll thank me.”

She expected a lecture on supply chains and logistics. Pricing index and pain points. Listen, son, if you really want to move some merchandise… She should have known her father would counter with a proposition of his own.

“My daughter says you’re smart,” said her father, turning to face him. “A hard worker, resourceful. Those are qualities that should be rewarded. There is no reason, in life, not to be comfortable. Have you considered other lines of work?”

“He’s an artist,” she insisted.

“Buy a man a fish,” her father said. “He is hungry again tomorrow.”

He refolded the price list, slid it back across the table.

“Ah!” Her father wagged a finger. “But if you teach a man to fish?”

A sales desk at a freight brokerage. That was the offer, the grand bargain. His response surprised everyone at the table, himself included. He stared her father in the eye and negotiated a higher salary, plus a week of paid vacation. It had been spontaneous, impulsive. Maybe it had been a mistake to order a third mimosa on an empty stomach. Still, he couldn’t understand why she was upset. He thought he had struck a good deal.

“It’s something to tide us over,” he told her. “It’s temporary.”

Temporary turned into twenty-five years. It put two kids through college. It was only ending now because two senior managers approached him with a proposal to buy the business. Their demand, really, was tantamount to mutiny. He found himself accepting it with relief. It took his wife longer to come around.

“It’s a fair price,” he told her.

“It’s so presumptuous,” she said. “You hired them. You trained them.”

“I think we should take it.”

“What if they offered to buy the shirt off your back? What if someone came here and wanted the house?”

“It’s a question of timing.”

“You’re right. You’re still young. You could start your own—”

“No,” he said, shaking his head.

He wished he could drop out, vanish overnight, the way he’d quit college in Texas. Halfway through freshman year, he taped a drawing to his door in the shape of Manhattan Island. His dorm monitor stopped him in the hallway and tried to make him take it down. He thought it was some sexual object, cigar-shaped and insertable, the latest entry on a long list of things those moonfaced boys couldn’t comprehend. “That’s where I’m going,” he said. “I’m already gone.” He hitched a ride to the station and never looked back.

His wife tapped her list with her pen.

“Dave Nichols?” he said. “Aubrey Singh?”

“Already on the list,” she said.

His father-in-law had been fortunate. He’d disappeared while sitting at his desk. The door swung open, the door swung shut. After a massive pulmonary embolism, nobody asks you to organize your own farewell event.

“While we’re in town,” his wife said, “I’d like to do a little shopping. This afternoon?” She laughed, seeing the expression on his face. “Don’t worry, I’ll be quick. Was there anything else you wanted to do?”

He opened his mouth to speak. There was so much he needed to explain. Everything, from beginning to end. He had been waiting for the right moment—and now, after weeks of inexcusable delay, he had lost all sense of how to begin. At work, they had found him slipping and finally seen right through him, but at home he had been going through the motions, undetected. He hoped keeping her in the dark would spare her from suffering, but it was less painful for him, too, to simply avoid the subject. He tried not to think about what that said about himself and his marriage. People who are good at hiding the truth have usually had some practice.

“Maybe,” he replied.

In his wallet he carried a folded-up referral from his physician. He had written it all down. He didn’t trust himself to retain the details. His short-term memory was a fallout zone. Things buried in the past, though, that was a different story. Lately entire scenes from his youth came back, vivid and bright. Lost moments were restored intact. He had been told disorientation could be a symptom of his condition, but that did not prepare him for how it actually felt when forgotten scenes, large and small, unspooled in his head like film stock from a secret archive.

Dr. Silva was a regular at the club who, from the moment they first met, believed he had found a kindred spirit. He was mistaken, but unmovable. He only wanted to talk about topspin and volleys and heart-wrenching drop-shots. Right up until the moment he broke the news.

“Your next question is survival rate,” the doctor said.

“Let’s just start with how to spell it,” he replied.

First, do no harm. What kind of oath is that, anyway? Why did some dingus in Ancient Greece, he wanted to know, set the lowest possible expectations for the entire medical profession? Couldn’t he have aimed a little higher? First, pull your head out of your ass! Listen to your patient, focus on the problem, and order a CT Scan on the initial visit instead of four more weeks of wait-and-see. By the time he saw the tumor on film, the pressure behind his eyes had been building for a month, gathering like a storm inside his skull. He held the transparency to the light, pointed to the toxic blob amid the brightness.

“This type of malignancy is infiltrative,” Dr. Silva told him. “It weaves new lesions through the brain like strands of a spider web. The cancer is, quite literally, rewiring your neocortex. You may experience headaches, mood swings, depression, delusions...”

“What kind of delusions?”

“Dissociations, hallucinations,” the doctor replied. “Rarely, psychosis. You should not be driving.”

He nodded, made a small noise.

“Do yourself a favor.” The doctor adjusted his glasses. “Don’t go mucking around online. The data is garbage. The mortality figures are outdated. There’s been a ton of new research and clinical trials. I’ve already spoken with a neurosurgeon, one of the best, someone who specializes in glioblastoma. He’s in the city at Sloan Kettering. He’ll squeeze you into his schedule.”

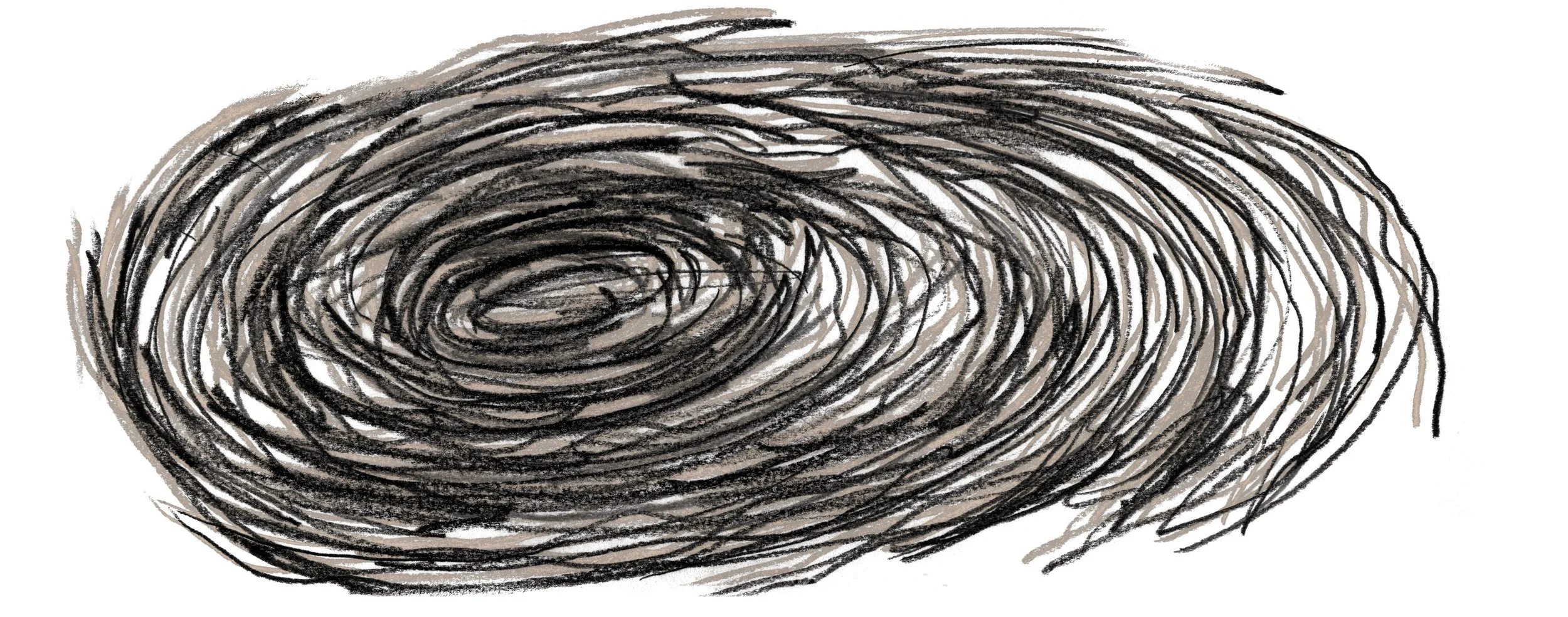

He had found himself sketching it at work. It emerged during conference calls, on the back of envelopes, in the margins of expense reports. A whorl of negative space, surrounded by concentric scrawling loops of black. It looked like a cat-five hurricane caught on doppler. He thought it would make a good subject for a painting. Large, abstract, violent. His first new work in more than twenty years. Self-portrait at 61.

###

His wife had been pursuing her own plans. She had made a list. She did not have much time to get it all done. For starters, she needed a new outfit for the retirement dinner. As a matter of principle, she always tried to look her best in difficult situations. She was still coming to terms with this one, and so far, she only knew half of it. Less than half, really. Her husband had been eased out, forced from the company her own father had founded. She knew there must be more to the story, something he was not ready to share, preferring instead to stew in his long silences. Regardless, she wasn’t going to sit on her hands. She tried to imagine how they might spend their time, alone and together, without the familiar distractions of the family business. She arrived at a solution during one of her morning walks, and immediately made arrangements for the renovations. A contractor would be coming in two weeks to clear out the spare bedrooms, removing carpet and adding a skylight.

She was proud of herself for keeping it a surprise. She had merely floated the idea, testing the waters.

“We could turn one of the upstairs rooms into a studio.”

“For what?” he said.

“Painting,” she replied.

“Pfft.”

“Or whatever you want.”

He seemed to think it over, before shaking his head.

“The light upstairs is terrible,” he said.

She did not argue the point. He didn’t always respond well to encouragement, but she knew he would warm to it eventually. What else was he going to do with himself? It took a few days until he came around. Over dinner, he proposed an impromptu weekend in the city. A grand tour of the great museums. The Met. The MOMA. The Whitney. She agreed without hesitation and booked a room at the Hilton in Times Square, paying extra for a high floor and a partially obstructed view of the Hudson.

After lunch, she led them across the lobby into Ancient Egypt.

Endless displays of immortal men, flat on their backs for two thousand years. Haughty cats and eagle-headed women lurked in the corners.

He read from a placard on the wall: “His heart, considered essential, was left in place, while the brain was removed through his nose and discarded, as its importance was unknown.”

“If we get separated...” his wife was saying.

In the next gallery a girl with a sketchpad peered over a large sarcophagus, leaning on her tiptoes. She was young and fresh-faced with a short pinch of a ponytail. He thought maybe she had come unattached from a school tour, one of the busloads of bored teenagers they bring in from the suburbs.

She propped the pad against her knee. Her pencil flitted across the page. Tentative at first with a sound of shuffling feet, then more confident, like measured steps up a steep staircase.

“You’ve got a good eye,” he said, with a glance at her work.

“Oh, thanks.” She smiled politely. “All it takes is practice, right?”

“That’s what they say,” he said.

She turned away and her pencil resumed its wandering. She seemed uncertain again, searching for the line. He watched her struggle to regain focus, pressing her thoughts like a fallen leaf between the pages.

“Sorry, I didn’t mean to interrupt,” he said.

“It’s just a sketch.”

“Keep going. I’ll get out of your hair.”

He backed away, somewhat embarrassed. He moved toward the next room. An old man, a museumgoer. He never thought he’d live long enough to see it happen. Passions reduced to pastimes. You waste your youth in a headlong pursuit and later it returns as a hobby. A way of distracting yourself from the inevitable.

He recalled walking at dawn with Evie Grossman. They had been in a group until the bars closed, then ended up sharing a booth at breakfast at 103 Restaurant on Second Ave. Their first morning together. He laughed at something she said about de Kooning, and the way she ordered her bacon, burnt. She liked the place because the owner let her order on credit. It was not far from her rent-controlled studio on Ludlow Street. Later she invited him inside for jasmine tea. She made it with honey. Her phone kept ringing but she didn’t answer. He was twenty-nine years old and had just confessed some minor tragedy, some careless act of self-sabotage and amateur alcoholism, when she told him she had been to a clinic the previous day to terminate a pregnancy. Her second. The first was when she was in high school and it preceded a trip to the psychiatric hospital. She went through it alone this time.

“It was a choice I made,” she declared. “I’m not going to fall apart.”

Her boyfriend kept calling, every ten minutes.

She was afraid he would show up at the door.

“There’s nothing left to say.”

“That’s rough,” he said. “I’m sorry.”

She shrugged. “Can I show you something?”

She had been building it in her room. A shadowbox. She showed him the picture frame with a drawing, unfinished, suspended on frosted glass. He studied the lines of ink layered across tissue-thin paper. It took him a moment. Gradually he recognized the scoop of forehead, the useless limbs, their uterine crypt. At her first appointment the technician offered to print her a copy of the ultrasound but she refused, and now regretted it. So she brought it back, the memory, the image, tending the tiny flame.

“It’s gorgeous,” he said.

“You make it sound like I painted a sunset.”

“That’s not what I meant,” he said.

“You don’t think it’s too precious?”

“It’s beautiful.”

“Because it needs to be beautiful,” she said. “Otherwise, what’s the point?”

He never considered her his competition. He should have known better. He should’ve listened to what she was saying. Instead he had searched for mentors at the Art Students League, men in the dusk of their careers, painters who trained protégés to protect their fading reputations. They were only capable of seeing promise in young men who looked like rebuilt classics of their own generation. He was a natural fit, nearly the same make and model. He cursed and smoke and drank like a state senator. He knew how to handle a hog-bristle brush. He could, on occasion, perform minor miracles on canvas, on sanded panels of plywood, on virgin sheets of hot-press paper.

He should have worked harder, he thought. He should have locked himself inside a room. He was filled with the terrible ache of all that was left undone.

He looked across the gallery at the girl with the sketchpad. He wished he could lift her and place her safely on the other side. You’ll leave school, he thought, and find a studio share with southern exposure and eventually people start noticing your work, and everyone around you begins to take off, your enemies will get agents, your girlfriend is going to be famous, but for you, maybe, everything takes longer than anyone expected, years and years, until people who seem to love you start asking when you’re going to straighten out and settle down. Maybe they never come out and say it, but you can see it written on their faces. The disappointment. You were so damn close, though. You could almost taste it. You just needed a way to see it through.

“Do not touch!”

He didn’t understand. He seemed to be staring down from a distance at his own two hands. They were pressed against a limestone slab. A feeling of chill numbness spread from his fingertips like frostbite.

“Move back, sir,” repeated the guard.

“Huh—?”

He felt a wobble in his bad knee. His leg nearly buckled.

He pushed away, rearing back from the stone coffin. Lidless and carved in inscrutable code, it remained rooted in place under his weight.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I didn’t mean to—”

His wife arrived in time to smooth it over. He waved away her questions at first, shaking his head.

“It’s just a migraine,” he told her.

“You’ve been saying that for weeks.”

“I’m fine. It will pass.”

“You need to see someone,” she said.

“I just need to rest my eyes.”

They retraced their route in reverse, holding hands, following the exit signs until they emerged into sunlight on the stone steps of the plaza.

On the street, a cab appeared as soon as she raised her hand.

She gave the driver the name of their hotel.

“Can you manage without me for an hour?” she asked her husband. “I need to make a quick stop before dinner.”

She was being coy, but he didn’t push for an explanation. He had enough to worry about. He still hadn’t told her about the appointment at four o’clock, but doubted he would be able to keep it anyway. It was too late in the day. He was tired. It would have to wait.

“Go ahead,” he said. “Have fun.”

The store was scheduled to close at five o’clock. She had called ahead, a special order. The salesperson assured her the easel, unassembled in its shipping box, would fit in the trunk of a taxi. She had also ordered a roll of raw canvas, stretcher bars in various lengths, and a set of sable brushes. She waited until she had reached the store to select the paint. It came in metal tubes like toothpaste. She knew her choices would be subject to criticism, so she aimed for abundance, choosing colors of foods, colors of seasons, colors of skin and viscera and teeth.

Her husband had brought her to this store before. He had been preparing for his first solo show, a dozen paintings at a small gallery in Soho. He could barely afford to buy cadmium or cinnabar but had already squeezed every pop of color from the containers in his corner of their apartment.

The work hung for three, maybe four weeks. Then he got a call from the gallery to come get it. He borrowed a truck from a friend who worked construction. She met him afterward for dinner at Fanelli’s, trying to make the most of it.

“The reviews were positive,” she said.

“Not especially,” he said.

“You’re being too hard on yourself.”

“Nothing sold,” he said.

“It’s your first show.”

“It’s my last show,” he said.

“Don’t say that, please.”

“Let it go, for chrissakes. What’s it matter to you, anyway?”

She saw faces turn toward them and away. Something swelled inside her and got stuck, forming a bubble in her throat. She swallowed before it burst. She refused to start crying in a crowded bar.

“You don’t have to yell,” she said, quietly.

“Then stop it with all this endless optimism.” He finished his drink. “It’s not working out. Don’t you get that?”

The next morning in bed he laid his head against her belly. Her hips were cliffs that beckoned shipwrecks. He kissed her, tenderly, cupping her between his hands. He said he was sorry, sorry, sorry...

He paused, pressed his ear against her belly.

“Don’t stop,” she murmured.

“Shh, I’m listening.”

“To what?”

“The ocean,” he said. “Something’s calling. A seagull, maybe.”

Her stomach growled again. She checked the clock, nearly nine. They had been up most of the night. He smiled and lowered his lips. She sighed and sank back against the pillows. He knew every inch of her body. Since the night they first met, he had been drawing her in his mind, studying the contours, the sharp dimples of her elbows, her modest breasts, her skinny toes. He traced every strand of her soft hair, high and low. At age twenty-nine, his attention had been full of pleasure and curiosity. It covered her like sunlight, bathing her skin with light and warmth.

Later she rose to make coffee. She heard a distant siren, receding. From his bedroom over West Broadway you could count every tree in the concrete triangle they had recently renamed Tribeca Park. Their oldest son slept in a crib in the kitchen. Their youngest was now swimming toward them across an endless sea of possibilities.

“Thank you for calling the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center...”

He sat alone on the hotel bed.

He pushed buttons on the phone until a woman answered.

“I have an appointment today.”

He gave his name, his date of birth.

“I can’t make it,” he said.

“Certainly, we would be glad to reschedule.”

Tomorrow, he could do it. Probably. Next week or the following.

“Sir? Are you there?”

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I’ll have to call you back.”

In the bathroom mirror he turned away in disgust. He had the face of a dead pharaoh, humorless and blank, stitched with fibers tough enough to outlast anything.

He left his shirt and pants in a pile on the floor, then turned on the shower. Minutes later, he turned it off. Soft light glowed through the glass doors.

Given the chance, he wondered, would he strike a different bargain? Erase the last three decades like a slate wiped clean by rain? Give up his wife and kids for a place in the permanent collection?

He tried to push the thought from his mind. It was an unforgivable question. He hated himself for asking it. And for not having the right answer.

The ventilation fan rattled out of balance, spinning overhead like the blade of a blender. He was so tired. He needed to lie down. He closed his eyes and slipped into some soft, shallow pocket of eternity.

It took a long while before his wife returned with her shopping bags.

He didn’t hear her calling from the bedroom. He didn’t hear her gasp when she found his body, stretched out in the bath, arms folded over his chest—

She touched his shoulder, his face. She searched for signs of blood, some visible injury. She couldn’t imagine he had settled there on purpose.

“Sweetheart, can you hear me?”

Startled, he opened his eyes. The porcelain was cool and hard beneath his back.

“If you want to take the boys to your parents,” he said. “I can come down for the weekends. I know this isn’t what you wanted—”

“What’re you saying?”

Their sons were grown, living in different states, other cities.

“Trial basis,” he said. “Maybe just a few months.”

“You’re scaring me.”

“I’m not giving up,” he said. “That’s what I’m saying. Do you understand? I’m going to make it. You don’t have to believe me, but you can’t make me choose.”

Frightened, she ran to the other room for her phone. She dialed for an emergency.

“My husband has fallen,” she said. “He must have hit his head. I don’t know. He’s not making any sense.”

She named the hotel, the room number. Come quick, she said.

She found her purse, put on her coat. She was not going to let go without a fight. Whatever was happening, they would get through it together, same as always, she promised.

He entered the room. The hair on his chest glistened wet.

“Sit down, please,” she begged. “Let me get you a towel.”

It took seven minutes for paramedics to reach their room. He waited at the window, looking out. The sun lay in retreat beyond the cliffs of the Palisades.

He could feel it finally happening. He was no longer afraid of failure. He had known all along his time would come.

John Powers lives and works in the Hudson Valley of New York. His writing has appeared in Brink, On the Run, Cimarron Review and the New York Times Magazine. More information at johnpowers.info.