Essay

On the Way Down

The Problem with the Homeless Problem

Essay By Sean Murphy

Illustrations by Sydney Lindman

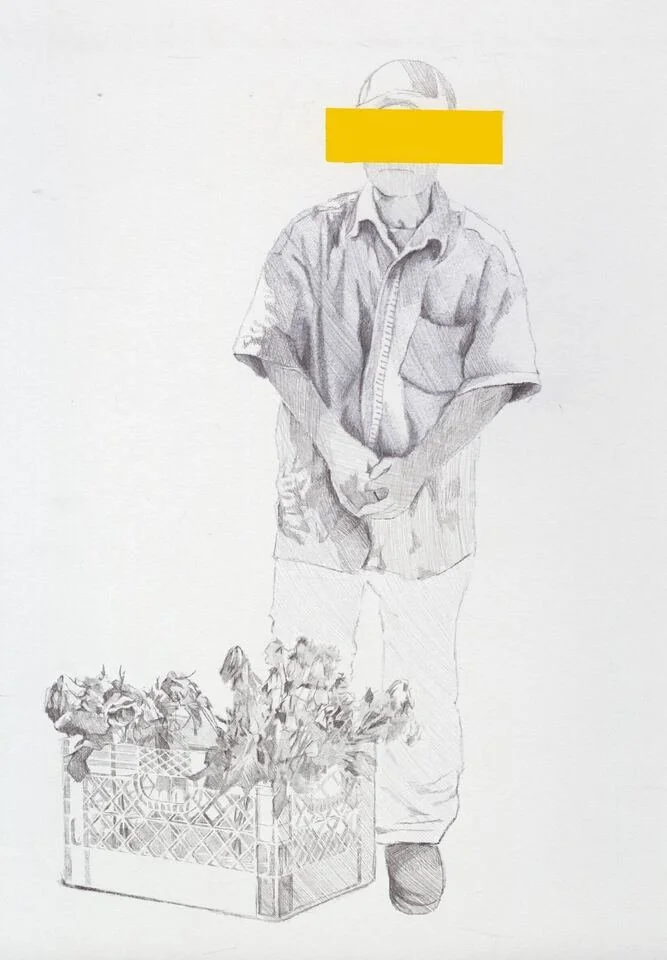

There’s a man who sits near the pumps at the gas station I drive by each day. He has about him a certain look—the meek, awestruck eyes, and apprehensive gestures that suggest he speaks little if any English. A stranger.

He remains respectfully distant from the customers—who incessantly fill their tanks, like bees returning to the nest before heeding the urgency of their instinctual obligations—but near enough to the action to remain in plain view. He sells flowers. Actually, he doesn’t seem to sell anything; he pretty much sits there, on an upturned milk crate, often from early morning until well in the evening, after the rest of the weary warriors have commuted past him, home from work and their worries of the wicked world. He silently plies his wares, content to play his part in the charade: he is not accomplishing much, he is begging, and the milk crate and collection of fading flowers at his feet communicate an inexpressible anguish. Please help me, his unscrubbed face, his unlaced sneakers, his oversized slacks, his filthy, fidgeting fingers—everything but his voice—all ask, saying what he cannot, and will not, say for himself.

* * *

My neighbor, whose name I’ve forgotten—if I ever knew it in the first place—and who, being roughly my age, never objects to and always answers my cordial salutations (chief, dude, bro, man)—is standing outside my door: I can see him through the peephole.

While I wonder if I should wait to see if he’ll knock again, he knocks again. It’s eight-thirty in the morning, what’s the worst thing that could happen?

“Hey ____,” he says, embarrassed or anxious. Or both. (At least he remembers my name.)

“What’s up, my man?” I say, not missing a beat.

“Listen, sorry to bother you. . . . You on your way to work?”

“Yeah, actually. Why, is everything okay?”

“Uh, yeah, listen, do you mind if I come inside for a second?”

I back up obligingly, resigned to roll with it. What choice is there? After all, I did open the door.

He corners me in my kitchen and asks if I know anyone who might be interested in buying a condo. His condo, for instance.

“I’m sure there are plenty of people who would love to live here,” I offer.

“Yeah, I know, but. . . I mean, do you know anyone who’s looking to buy a place?”

“I’d be happy to ask around, you know, put the word on the street and whatnot.”

“Yeah, that’d be cool, I’d appreciate that.”

He looks away and it’s my turn to say something.

“Everything okay?”

“Yeah, well, I got laid off, you know? So I’m just gonna move home for a while, with my folks. You know, till I get my shit straight.”

“I hear you,” I say as encouragingly as possible, but it’s only half true. I do hear him, but I also hear the voice inside my head, which is processing this situation and repeating the verdict: Not good, not good, not good.

He is sweating, his hands—they seem puffy and pale; I’ve never noticed before what unbelievable meat hooks he has, though admittedly, the only times I bump into him are in the hallway as he disappears into his end unit with a case of Miller Lite cans under one arm, a bag from McDonalds or some other fast food chain in the other—his hands, exhibits A and B, are shaking like the lid on a boiling pot, they are very obviously not obeying their master. Before I have half a chance to put two and two together, he interrupts my internal assessment and looks at me searchingly.

“Hey, you got any beer?”

* * *

Hey brother, can you spare a life, the woman moving past me does not say.

I’m in too much of a hurry to stop (like always, like everyone else getting on and off the subway), but there is something so familiar about her that I’m compelled, despite everything I’ve learned, to pause and look back: she is still there, off to the side, shabbily clad, immediately recognizable by her contrast to everyone around her; she wants to approach one of these businessmen, but all of them are walking too fast, too deliberately, too purposefully. Getting from Point A to Point B so they can get paid.

Automatically, the subway station doors move aside, and frigid air greets us all. It takes about five seconds (as always) to feel the cold and then the dread: it wouldn’t take much to become lost in a strange city, alone, broke. Quiet in the corners, huddled under bridges, working frenzied crowds for a friendly face, hoping for the handout that never comes.

I don’t have any lives to spare, but I’ll dig into my pockets and give till the sight of this stranger hurts a bit less.

* * *

You got any beer?

The words, which I can’t believe I’m hearing, hang in the air. At eight thirty-three in the A.M., there is only one possible answer to a question like this: “Sure,” I say.

I open the refrigerator and remember: I drank my last beer last night, which makes me a liar.

“Actually, I don’t,” I start, but it seems that will not suffice, so I hold the door open and let him inspect for himself, which he does, making us both feel better—or worse—depending on how you look at it. He accepts this answer but is clearly not satisfied with my response.

“Oh. I have plenty of liquor, if. . . ”

“Yeah, do you care if I take a shot of something?”

Are you sure you’re okay? (To myself I say this.)

A pint glass is obviously inappropriate, so I grab a juice glass and put it down on the counter, sliding it over to him like a bartender from a black-and-white western. He has eagerly grabbed my fifth of single-malt, and I tell him to help himself. He pours a generous, bordering on unbelievable, belt of my booze and inhales it in one febrile motion. This is strictly business.

“Better?” I inquire, and actually mean it; I want to know.

“Uh. . . do you mind if I get another one?”

“Hey bro, knock yourself out,” I say. Stupidly.

He doesn’t notice because he’s too busy securing the second round in case I change my mind at the last second. Even the sweat on his forehead seems relieved. Although I know exactly what time it is, I can’t help myself from looking up at the digits blinking on my oven: 8:34.

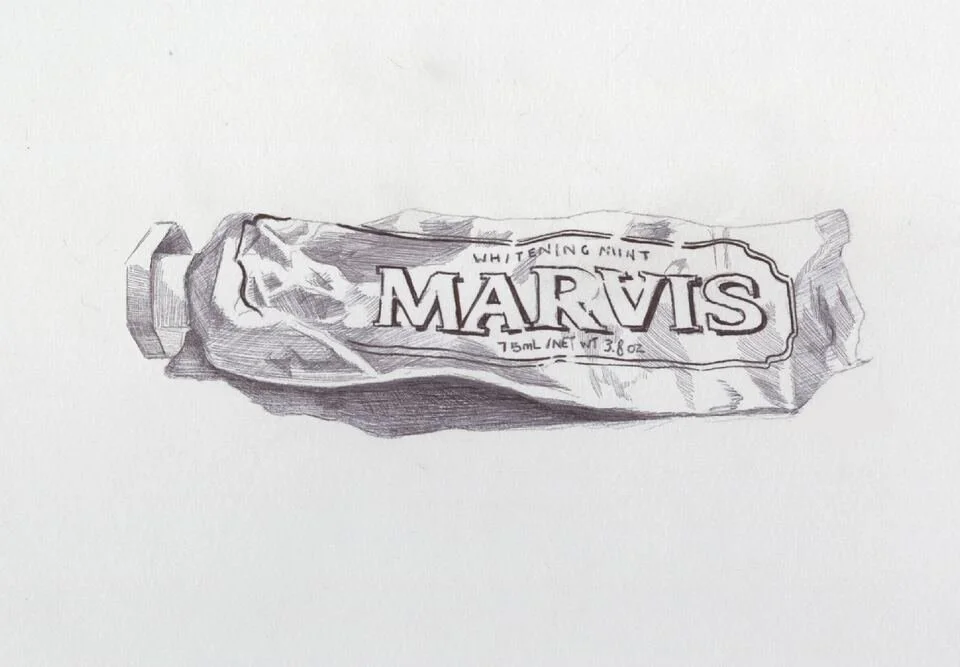

He looks at me and nods his head, expressing gratitude with his burning eyes. The eyes never lie. Then he snatches a tube of toothpaste out of his front pocket, puts it up to his mouth, and pulls the trigger.

“So, you wouldn’t mind asking around, you know, just see if anyone is looking to maybe live here? I’ll cut a deal.”

“No problem.”

“I’ll hook you up with a finder’s fee too.”

“Oh, don’t worry about that man, I’m happy to help.”

Not good, not good, not good.

“Let me give you a card,” he says, putting the toothpaste back and reaching into his other pocket. I’m surprised, despite myself, that between the shaking and the sheer size of his hands, he can even fit them into his shirtsleeves.

“Fuck,” he says, frazzled or furious. Or both.

“What’s up?”

“I left my fucking cards in my place.”

“Well don’t worry about it, let me just write your number down and. . . ”

“No, let me run and get them, and you can hand them out and shit.”

“Okay.”

* * *

Who was he?

I think the same question each time I see him (once a week, sometimes more often): the same man in the same spot, holding the same sign that tells everyone who he is now—“HOMELESS VETERAN”—prompting me to wonder: who did he used to be? He has worked this intersection for several months now. The cardboard sign he holds asks us to put pocket change in his plastic cup. Even if he isn’t really a veteran, I think, he has been homeless long enough to be one now; or if he is not actually homeless, he has been acting the part long enough to earn the title. Either way, it is time for a promotion.

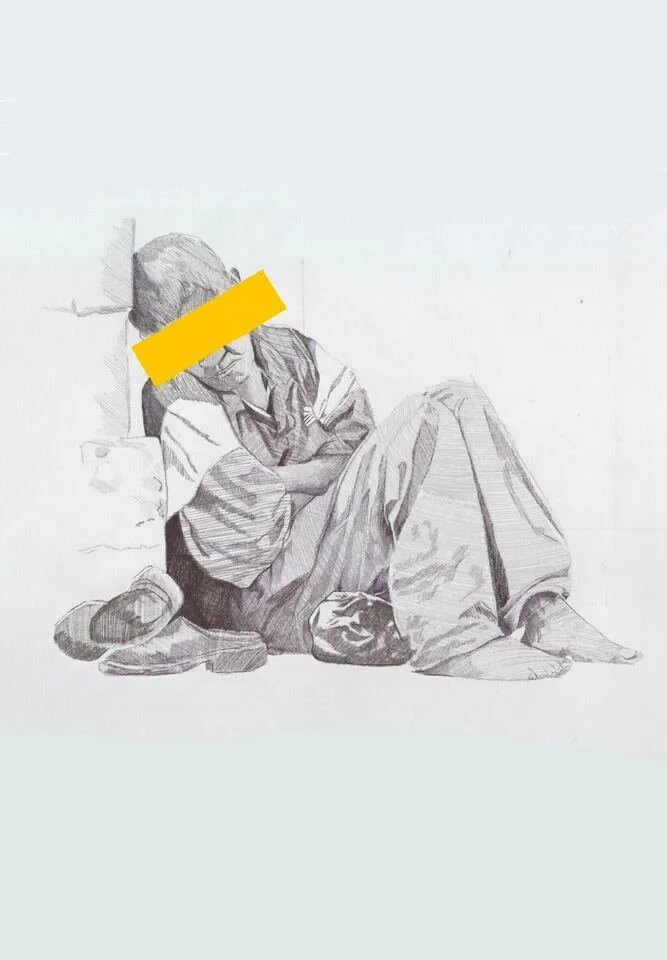

And so, I think, this is the problem with the homeless problem: it isn’t the ones who hustle or approach you who are truly down and out; they’re the ardent ones, still showing signs of life, maybe even hope; it’s the ones you never see, even when they’re sprawled on the concrete right beside you, the ones who are down, the ones who are out, the ones who have nothing to ask for, nothing to say, nothing to do except wait, sit it out until the inevitable end. It is the ones you can afford not to be afraid of, the ones who can’t not even hurt themselves, because they’ve already dug as deep inside as their ashen fingers can reach, the ones too dead to tear out their own hearts, but not dead enough to unloose their souls, the ones who have learned (too late) that death is only impatient for the fools who fail to acknowledge it, it has all the time in the world for those whom the world owes nothing except the decency of an overdue release.

* * *

I wait (too long) and go down to get my neighbor’s business cards myself.

On the way, I think: Gambling debts? Drugs? Or both?

Drugs, it must be drugs.

Whatever it is, it’s something I know I want no part of.

* * *

Could that be me?

A primal foreboding, an ancient fear. Who knew how it happened, who could make sense of it? And yet. These people do not wake up one random morning, on the streets and out of their minds. Or do they? If you believe the signs the man on the corner holds, the government did this to him—and could do it to anyone else: that is his message, his mission.

The problem with the homeless problem is that so many of these lost souls are chasing something they can no longer name: memories. Or, even worse, it is the memories that are chasing them, speaking in tongues they long ago ceased to understand.

* * *

I knock on the door.

It opens, quickly, and my neighbor walks out, shutting it behind him. Apparently, I’m not supposed to see inside. Perhaps I don’t want to see inside.

He follows me into the hall.

“Hey ____, I appreciate anything you can do.”

“No problem, dude, I’m happy to help.”

“Listen,” he leans in close. “Do you mind if I grab another shot?”

“Sure, man.”

I’ve already locked my door on the way out, so I let myself back in, tricking my dog into thinking a full day has already passed.

The bottle and glass are still on the counter.

“Do you mind if I pour a stiff one?”

“Help yourself, chief.”

You want to take the bottle with you? (To myself I say this.)

He pours a shot that would give Liberty Valance pause, polishes it off, and then pulls out the toothpaste from his holster.

I ask no questions; he tells no tales.

I tell my dog to hold down the fort (again) and my dog looks confused or disappointed. I lock the door (again) and escort my soon-to-be-ex-neighbor out.

“Thanks again, man.”

“Okay, man, take care of yourself.”

“Give me a call if you hear anything.”

“Will do.”

Both of us seem to understand, as we go our separate ways, that we’ll never see each other again, and we are each somewhat deflated, probably for opposite reasons.

* * *

A memory:

When I was a kid, (I couldn’t have been much older than ten) my father and I had a layover in Newark Airport. Even then, I was perceptive enough to understand that this was no place I ever needed to return to voluntarily.

An unassuming older man (at any rate, he was noticeably older than my old man, which made him old) sat in one of those impossibly plain plastic chairs, with his pants leg rolled up. It wasn’t until we got closer that I realized two things: he was alone, and he was scratching at a series of scabs on his shin. For some reason he looked our way the moment we passed him, and after sizing us up, he stood and amiably approached my father.

“Sir, did you need someone to help you and your son carry your bags?”

“No thanks, we’re okay,” my pops replied, looking ahead and picking up the pace.

The man was persistent. In the space of fifteen seconds, my father denied him three times. My emotions slid from the appreciation of possibly having someone carry my suitcase for me, to the vague, uneasy suspicion that my father was being somehow rude, a jerk, to the unsettling awareness of recognition. I sensed something I’d seen plenty of, but never before in any person older than myself: fear. I saw it in his eyes, and felt it in my insides.

As we walked away my old man waited until we were at a charitable distance, then looked at me meaningfully and offered the somber assertion: That’s as low as you can go. I asked him to elaborate, as was my style, and he was either unwilling or unable to add anything to his observation, as was his style. It wasn’t that I didn’t understand what my father was saying, I understood him perfectly. It was because I understood him that I needed him to say more, to talk to me a little longer about it, about anything—anything to interrupt that silence and the sudden thoughts that accompanied it.

* * *

It’s easy to believe that people like this exist for our sakes: they are dying lessons on how not to live, warnings of what could happen if you weren’t careful and found yourself scratching at scabs in the world’s ugliest airport. Or enlist, get used up, and ask not what your country can do for you, because you’ve already received the answer. We forget, or we don’t allow ourselves to entertain the idea that these people have histories, that these shadows and signposts don’t happen to serve a purpose for anyone else—they were once actual people themselves and still are.

I realize, now, my father was wrong about one thing. That’s not as low as you can go. You can go lower, a whole lot lower. But perhaps it’s more disturbing to see the ones who are on the way down, it’s somehow easier to accept the ones at the bottom of the ocean; it’s the ones who are sinking, who are still within reach, who are drowning noisily in front of you, who sometimes have the temerity to ask you to hold out a hand. These are the ones we can scarcely tolerate, because every so often we look at them and see ourselves.

Sean Murphy is founder of the non-profit 1455 Lit Arts, and directs the Story Center at Shenandoah University. A long-time columnist for PopMatters, his work has also appeared in Salon, The Village Voice, Washington City Paper, The Good Men Project, Sequestrum, Blue Mountain Review, and others. His book Please Talk about Me When I'm Gone was the winner of Memoir Magazine's 2022 Memoir Prize. seanmurphy.net @bullmurph.