Essay

Imagining and Fathoming: A Grief Chronicle

Essay By Jannie Edwards

Illustrations by Constanza Pacher

There is a story of a woman whose anger kept her alive. Alive in the way a ruptured wasps’ nest is alive. Sirens. Red Alert. The Worst had happened. Her child, unable to bear his life, had ended it. Why hadn’t the world stopped? Everything hurt. Air. Beauty. Touch. Sympathy. A card with a picture of an island lighthouse surrounded by crashing waves: Just a note to say I’m thinking of you. The deepest hurt was the silence of those who could not bring themselves to speak of the child’s death. The mother was exiled in a migrained cell, her grief a life sentence.

* * *

The woman in this story is really you, my friend of decades.

When I first heard the news, I texted you to say I was bringing soup and bread. Knowing you are deeply private, I said I would leave it on the doorstep if you were not ready to see me. But you opened the door and we wept in each other’s arms, then sat at your table while you showed me your son’s amazing art.

When we spoke on FaceTime a few weeks later, your face was hard, your talk full of grudges. Then I heard from a mutual friend that you were irreconcilably angry, that you wanted it to be known you wanted nothing to do with any of your old friends. No texts, no phone calls, no emails, no gifts, no cards. No Trespassing.

I try to imagine living with the kind of burning anger I imagine you are experiencing. When I think of the few times in my life when rage has overtaken me, I realize that for me, rage manifests as deeply cold, a slow glacial scouring. Did your anger become a fierce psychic fuel that kept you alive in the scald of raw grief? But what else could you do but stay alive? There is another child: a younger son.

* * *

I cannot imagine what you’re going through, people say. Such a tragedy. I cannot fathom, some say, alluding to nautical depths of suffering as darkly huge as the Mariana Trench.

But what parent has not imagined losing a child? I have imagined it. Years ago, I wrote a poem about listening to a wild blizzard, as if in this kind of storm I might hear echoes of my own fears, the greatest of which was the death of a child. I imagined how the news might arrive: on the phone, at the door, maybe in the middle of an otherwise uneventful day. How that news would tilt the axis of my world irrevocably. How the mother—how I—would open my mouth and howl a primal scream that would join with the howls of all mothers who have lost children. So many mothers. So many grandmothers. So many children lost.

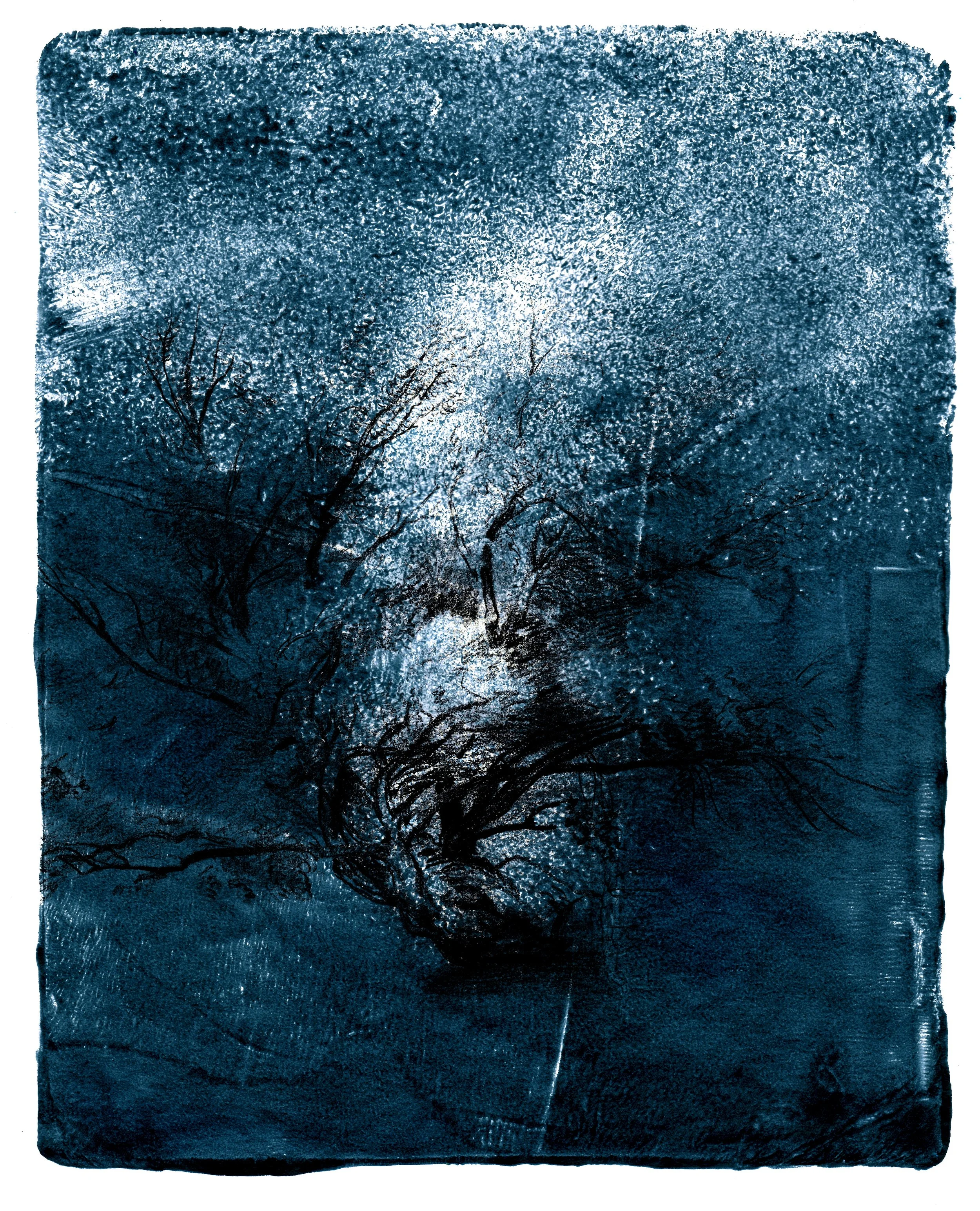

Constanza Pacher, Six Fathoms Deep, 2024

* * *

I remember watching Quebecoise director Sophie Deraspe’s film Antigone with my fourteen-year-old grandson, our last outing before the pandemic lockdown. The ancient tragedy is reimagined as a refugee story. The father and mother have been murdered in a war in an unspecified Middle Eastern country. The grandmother, Méni, brings the children—Antigone, her sister Ismene, and the sons, Polynices and Étéocles—to Montreal. A run-in with police results in the shooting death of Étéocles. Polynices tries to flee but is arrested. Convinced her brother will not survive deportation to their home country, seventeen-year-old Antigone sacrifices her university scholarship and her future to disguise herself as her jailed brother so he can escape.

Antigone’s grandmother, Méni, who has warned her granddaughter not to tempt fate, is forbidden to speak to or meet with her after her arrest, so she stakes a chair the exact distance from the juvenile detention center prescribed by restraining order. She plants herself there and sings. She weaves her aged voice into the depths of her grief to sing to Antigone inside the jail. A crowd gathers around the old woman. Day after day, she sings.

Through my tears, I whisper to my grandson in the darkened theater, “I would do this for you.”

What do we have to offer those who suffer? Song. Soup. Bread. Just a note to say I’m thinking of you.

* * *

Such a tragedy. I cannot fathom.

The audience watching Sophocles’ Antigone in 441 BC knew what would happen: that’s the first crucial part of this tragedy contract. The second requirement is that the characters don’t know right away. In order for this tragedy to play out purposefully, it is necessary that the audience know more than the characters, at least at the outset. How the characters gradually and shockingly come to know their fate, how they respond to this knowing—that is the vital engine that drives classical tragedy.

What signs do any of us see? What knowledge do we carry?

In his Poetics, Aristotle said that pity and fear should be the defining experiences of tragedy. That if the tragedy were “serious, complete and of a certain magnitude,” we should feel the pained awareness of undeserved anguish experienced by others, and this identification should make us fear that a similar misfortune could also happen to us. Essential to this conception of tragedy is the sense that the misfortune is both undeserved but also inevitable, that it cannot be side-stepped by cunning or care. And deeply nested in this sense of the inevitable is what Aristotle called catharsis—that the pity and fear we feel for this suffering is a kind of cleansing, a purging.

But how do we accept the tragedy of a child’s suicide? How do we accept a child – even an adult child—as an autonomous being whose suffering is so insoluble that they choose not to live? Is it even a choice? And what of those stranded by this kind of death? The terrible afterward. There is no catharsis here.

* * *

There are times I have been a helpless witness to my own children’s suffering.

Each of our three children has experienced serious injury or a close encounter with death. The youngest tripped running to a soccer game, breaking her arm so badly the bone pierced the skin. Her scream stopped us as we drove to park the car. Her limp, bloody arm dangling. Her stricken face.

At thirteen, our middle daughter was hit by a truck on her way to school. Twenty minutes after I kissed her goodbye, the doorbell rang. I opened the door to find my daughter covered in blood. Miraculously, she survived with a small cut above her right eye that required seven stitches. Years later, she had a small lump removed from the back of her skull. Amazed, the surgeon showed her a piece of gravel encased there. The tiny rock had lodged there for years, the aftermath of being dragged under the truck for several yards as the truck driver backed up after striking her.

The eldest was robbed twice, both times at knifepoint. The first time was in Oaxaca. Two robbers stole her backpack holding everything essential—money, passport, ticket home. She was convinced she’d narrowly escaped being raped. What haunted her was a sense that her mind had separated from her body and that she could not summon a scream. The second time was in Quebec, where she’d gone with her boyfriend on an extended summer program to learn French. Her boyfriend was badly cut trying to defend himself against the robber’s knife.

There’s a reason we call luck dumb. I’ve come to think of luck as a force that moves through the world with a staggering, lurching gait. For me, luck has come to mean less about windfalls or jackpots and more about close calls, near misses.

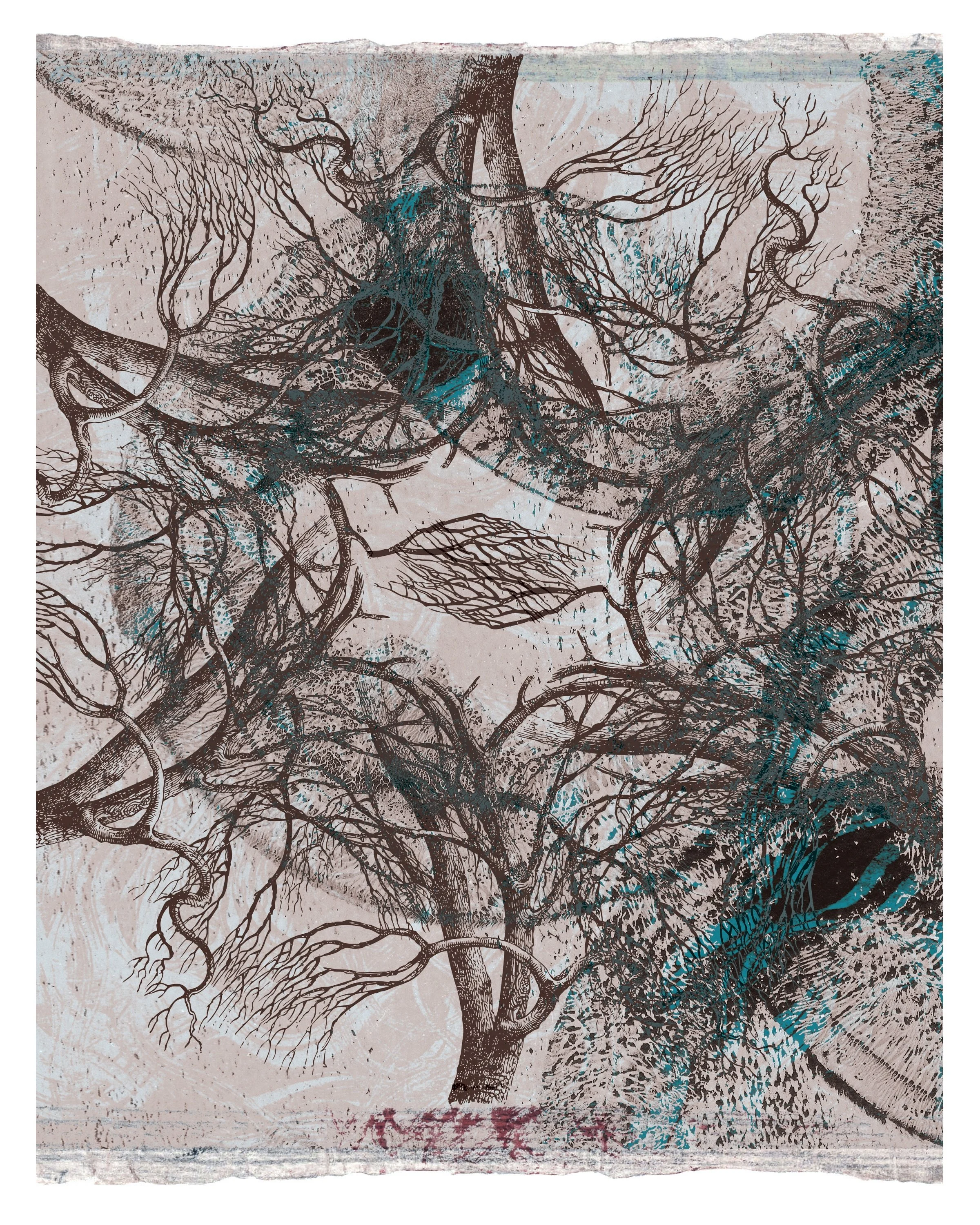

Constanza Pacher, No Trespassing, 2024

* * *

My eldest daughter, a mother herself now, reminds me of a poem I wrote years ago titled “What to do when you lose a daughter.” How could I have forgotten writing this? Was it during the time of so many close calls? Or earlier, when this first daughter was struggling in her teens and her struggle seemed beyond my reach or help. A daughter whose anger flared when I asked her to consider seeking professional help.

I find the poem buried in an old file—at least two computers ago. It imagines a grieving mother committing to a long ritual of digging the earth, planting and tending willow trees.

Reading the poem at this remove, I see that I have tried to imagine how I, how any mother might possibly survive after the death of a child. The poem imagines moving from the initial shock of the tragedy into the long afterlife of grief through a ritual of digging and planting willow trees.

I remember something poet Jane Hirschfield said—that when faced with the uncomfortable confusion of the world around us, when faced with experience that is unfathomable, poets try to fathom—that this psychic fathoming is an accounting beyond numbers, beyond logic.

How did this poem arrive?

In the first spring we spent in one of my childhood homes, my mother got a local man to dig deep holes in the packed earth of the bare backyard. In each pit she planted a single willow stick. The effort seemed utterly impossible, the sticks so fragile. But over the five years we lived there, we saw these slender sticks grow into saplings. And when I returned for a visit a decade later, the willows towered over the six-foot high fence.

Another memory: talking with a man in Wales who had been working with troubled, at-risk youth. They started by growing gardens of flowers and vegetables, and then they began making living sculptures out of fast-growing laurel willow. He showed me pictures of these sculptures evolving over a dozen years. A strange, mythic animal with horns. A twisted circle. A gnarled hobbit hut with a wooden door.

Here is the poem.

* * *

What to do when you lose a daughter

i.

Make a willow hut from your grief.

When the ground thaws deep enough

dig a trench in a circle wide enough

to lie down in. Dig it to your knees.

This will be the hardest part.

You will want to throw yourself down.

But you will keep on digging

through the black wound of your rage

through the raw wound of your love.

You will keep on digging

until the only voice that makes sense

is the mantra of your muscles

growing hard under your toughening skin.

One day, the trench will be finished.

But you have just begun.

Until snow completely fills the trench,

feed the earth with scraps from your kitchen—

that way, you will be reminded to eat.

Remember how when she was growing

in your private sea,

your body’s law was to give, hers to take.

Remember how you obeyed.

The first winter will be long and dark.

You will turn your face to the wall.

ii.

When the days begin to breathe warmth

again and ice starts to break up,

go in the early morning to a river you know well.

Sit by the river.

Listen

as it begins to wake up –

ice creaking and banging,

sound of running water.

Remember how you watched her sleeping

and when her eyes opened,

she looked right into your eyes,

without alarm, like an old soul.

As if she knew it would be you

and you would be waiting.

Just before the sun rises

when you still feel frost’s skin,

this is when you must cut your willow branches.

Pick the branches that look dead.

iii.

Plant the sticks in the trench

a hand-width apart, your fingers stretched

as far as they will go.

Water the sticks often.

Watch the sky for rain.

Wait.

You will feel invaded by weariness.

You will feel old as stone.

iv.

One day, you will see the first buds.

Perhaps there will be a storm brewing,

thunder on the move. Perhaps

you will hear your first robin.

You must be patient.

Snow can come in May.

v.

In a few years, faster than you think,

the sticks will be saplings.

In the spring just as they are budding

now you must begin to weave them.

Plait the supple, scrappy branches

as you gathered her hair into a thick braid

that day by the sea when she got her first

woman’s blood and you swam together

until you felt cleaner

than you’d ever felt before.

Tie the woven branches into a dome.

vi.

You will be amazed at how quickly willow grows.

In a few more years, the thickened trunks

will close the hand spaces of your planting.

In the full leaf of summer

you will not be able to see the sky

through the green roof.

Willow suckers will crisscross the floor.

Children will want to play there,

share cool secrets.

You will not mind if they do.

vii.

In the early spring,

you will lie down there

and in late fall too, the hinges

of your hips creaking.

The best is deep winter

when the silver ribs of the roof

pattern the cold, dark sky

spilling over with stars

and the moon is a scythe cast in ice.

You move your arms and legs slowly

up and down

apart together

This is what you have been waiting for

this mute push toward light,

this dark reaching

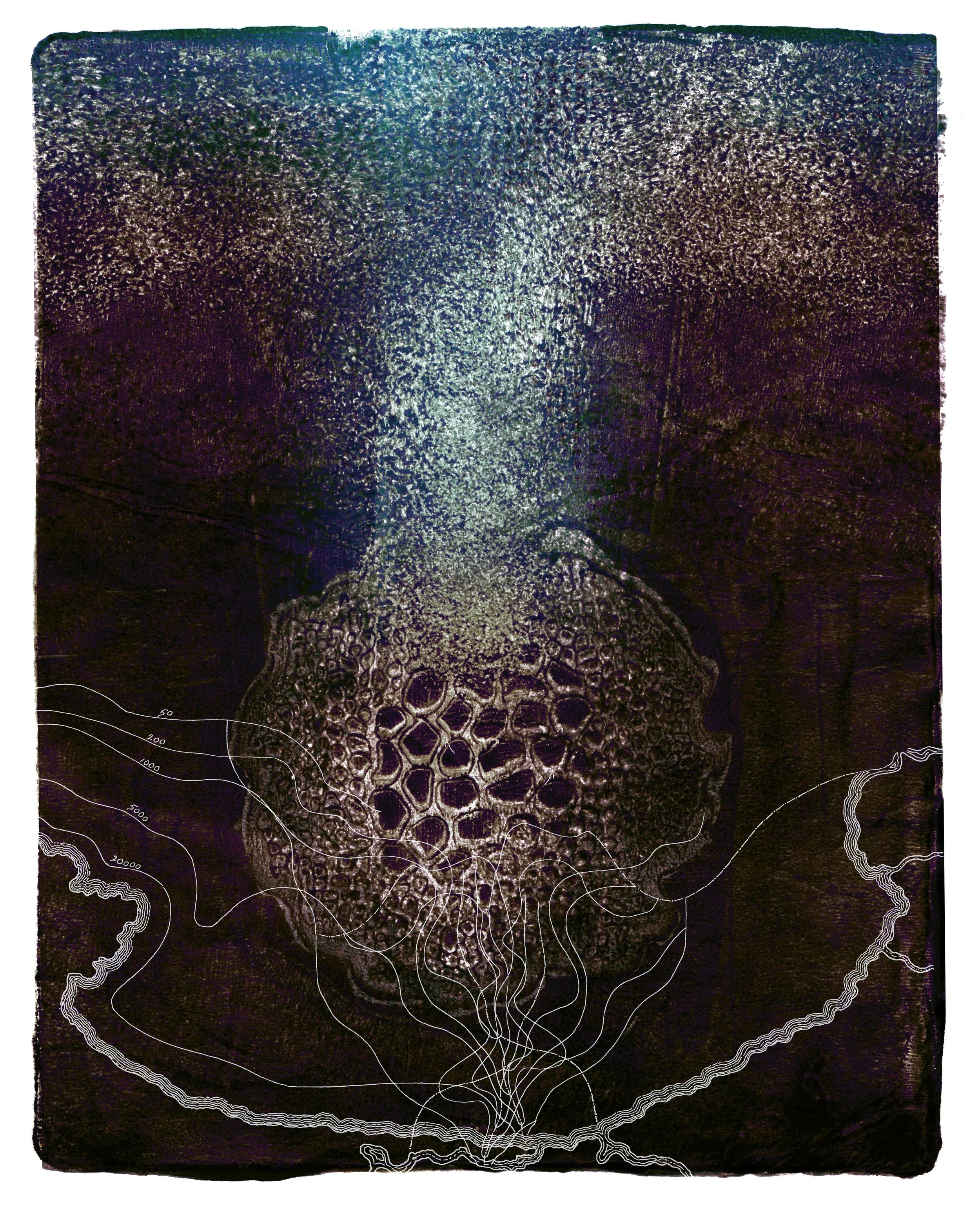

Constanza Pacher, Growing Anew, 2024

* * *

Reencountering this poem years later, I find it strange I wrote it in the second person. Did I imagine I was speaking to another mother?

No, this was a conversation with myself, a way to create psychic distance from such profound grief, even imagined. There is something compelling about this ritual. That in the digging, planting, and waiting through seasons for the willows to grow, then shaping them into shelter, the effort and expectation might offer some peace.

When I reread the beginning of this essay, I see that my old instincts of imagining turned my friend’s tragedy into a story: “There is a story of a woman whose anger kept her alive.” Is this distancing, this story, how I imagined I could be with my friend whose life had burned down? Did I imagine that story was a safer way to approach grief so fierce it has turned my friend away from the world?

Stories are wondrous things, says author Thomas King. Some stories have come into my life as gifts. My mother’s faith that those willow sticks would grow into shade and shelter. The Welsh man’s story of working with troubled kids to make art. Stories can sustain and heal, but they can also be dangerous. You have to be careful, says King. Once told, a story is loose in the world. It cannot be untold.

And now, as our separation stretches into its second year, could I risk sending this poem, this essay to you? I worry they might hurt you more, that you might slam the door in my face. Or maybe my greater fear is what might happen if you opened the door to meet me standing there.

* * *

In the first raw months of our separation, I’d wake exhausted and distraught from dreams where I’d catch a glimpse of you in a crowd, then desperately race to catch up with you, always in vain. Last night, the dream changed.

We were walking together on the gravel banks of a big northern river. It was very early spring—the sun struggled to breach the overcast horizon and scale the frost-covered bank. The river was still locked in ice but not for long; the days were lengthening, the river shifting.

We looked like the old grandmothers, the babas I saw in a documentary about Chernobyl where ancient, kerchiefed women had moved back into their homes after the nuclear reactor failed. We are walking hunched over like those crones who defied the No Trespassing/Nuclear Hazard signs.

We were cutting willow branches.

Constanza Pacher, Waiting Through Seasons, 2024

Jannie Edwards writes from Edmonton/Amiskwacîwâskahikan, Alberta, Canada, on Treaty 6/ Métis Region 4 lands. Her most recent publications are the chapbooks Blues for a Rare Moon (Alfred Gustav Press 2023) and Learning Their Names: Letters from the Home Place (Collusion Books 2022), letters exchanged across the country by two Settler women during a pandemic year that explores their evolving relationship with a beloved five-acre off-grid homestead in northeastern Alberta.

Constanza Pacher is an educator and visual communication designer born in Argentina. She teaches in the Bachelor of Design at MacEwan University, in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. In her work, she combines analog and digital techniques to create layered images that evoke emotion. Constanza has been honoured with two teaching awards (Distinguished Teacher, MacEwan, 2016; Honourable Mention, RGD Western Canada, 2021).