Mastry Calls Out the Western Canon

The sensational Kerry James Marshall retrospective heads to LA.

———

By Yvonne Hardy-Phillips

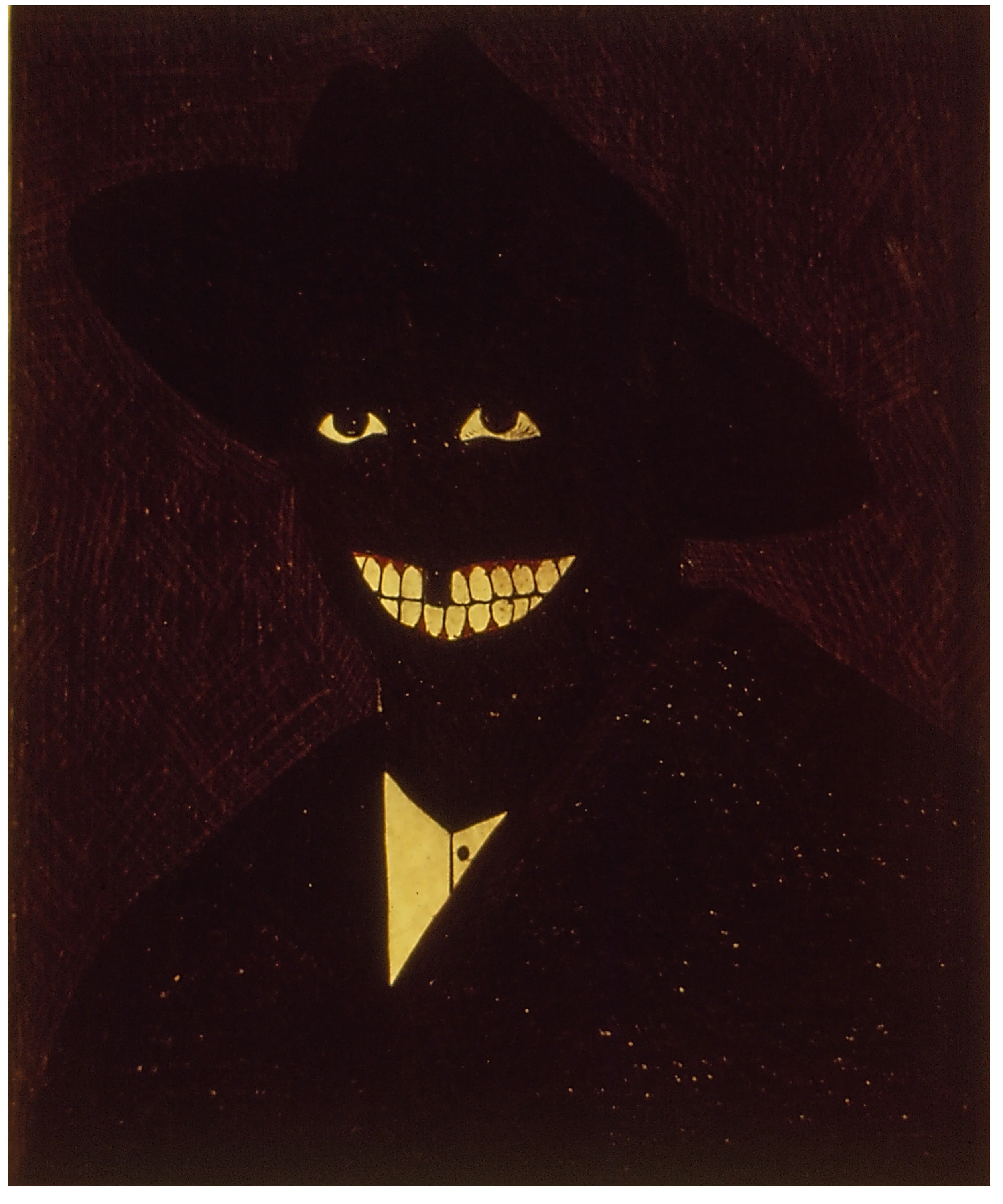

Kerry James Marshall, Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of his Former Self, 1981. Egg tempera on paper, 9 × 7 in. ©Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

If you missed the Kerry James Marshall show at the Met Breuer in New York, you have a second chance to see it this summer. One of the most sensational American art exhibitions to have opened in 2016, Mastry has moved to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, where it will be on view through July 3. This mid-career retrospective is a show for the ages, arriving at a time when museums and collectors the world over are rushing to acquire the meagerly collected works of important African-American artists. For too long, the art world neglected the brilliance of the black art aesthetic, but it appears that the dam has burst and with good results.

Mastry challenges viewers to confront their ignorance of the black experience—in the "real" world, and in contemporary art production. The show features eighty works of art, nearly all of them paintings, including intimate, small-scale portraits and expansive narrative images, monumental in size. In cinematic tableaus, layered with personal remembrances, storytelling, and art historical references, Marshall has indelibly painted black folk into the history of American art, and into our visual memory.

Born on October 17, 1955, in Birmingham, Alabama, Marshall moved with his family to South Central Los Angeles in 1963 two years before the Watts race riots. His passion for art showed early; as a boy, he acquainted himself with all of the art books in his local library. At the age of ten, during a class trip to the Los Angeles Museum of Art, he realized that he would someday become an artist himself. In the years to come, he would take it upon himself to hone technical expertise in the craft of painting, and to immerse his imagination in the history of art and the work of master painters. Marshall graduated from the Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles in 1978 and, nine years later, participated in a residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem. He moved to Chicago a short time later where he has since lived, painting steadily, and creating a body of work for which he was honored with a MacArthur Fellowship in 1997.

In becoming acquainted with Marshall’s oeuvre, there is perhaps no better place to begin than A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self. Executed when he was twenty-five, this painting marks his departure from a brief, experimental emphasis on abstraction. He has dismissively described his abstract output as “pushing around paint”. In Shadow of His Former Self, he paints with a greater purpose. White eyes, teeth, and a triangle of a shirt at the throat shine garishly from this spectral, black-on-black self-portrait. The figure wears a rakish hat and the clownish grin of someone who may not know he’s the butt of some insidious joke. The figure calls to mind the literary potency of Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man, corresponding as it does to the invisibility of the black figure, in the art canon and elsewhere.

Since its creation in 1981, this haunting image has achieved iconic status, in part because it marks a breakthrough in Marshall’s career, signaling his commitment to figurative painting. It also displays what would become a signature style—his reliance on only black pigments when rendering black figures. Excluding black pigments from other areas of his canvases, Marshall paints his figures with four shades of black so that they achieve heightened definition. This self-conceived color formulation characterizes Marshall’s work with a unifying visual force.

Early in his career, the dearth of images in museums and galleries that portray black people provoked him to adopt the tradition of history painting, yet to infuse it with the familiar imagery of black life and lore. Marshall excels, and is most adept, at monumental narrative painting. He developed interest in this form through close study of European “master painters” such as Courbet, Corot, Daumier, and Millet. “If you look at the historical narrative of art, we do have to contend with the narrative of the ‘old master’,” Marshall says in a video-taped interview for the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. “I had to recognize [that] in the pantheon of ‘old masters’, there are no black masters.” So he worked with a single-mindedness to learn from these painters, “to close the gap between what they done and what I was doing.”

These efforts were not personal; self-expression was not his aim, he implies in the interview. Rather, he recognized his responsibility to paint black figures in as many idealized contexts as necessary to normalize and dignify this visage to the art-viewing public. This became his project.

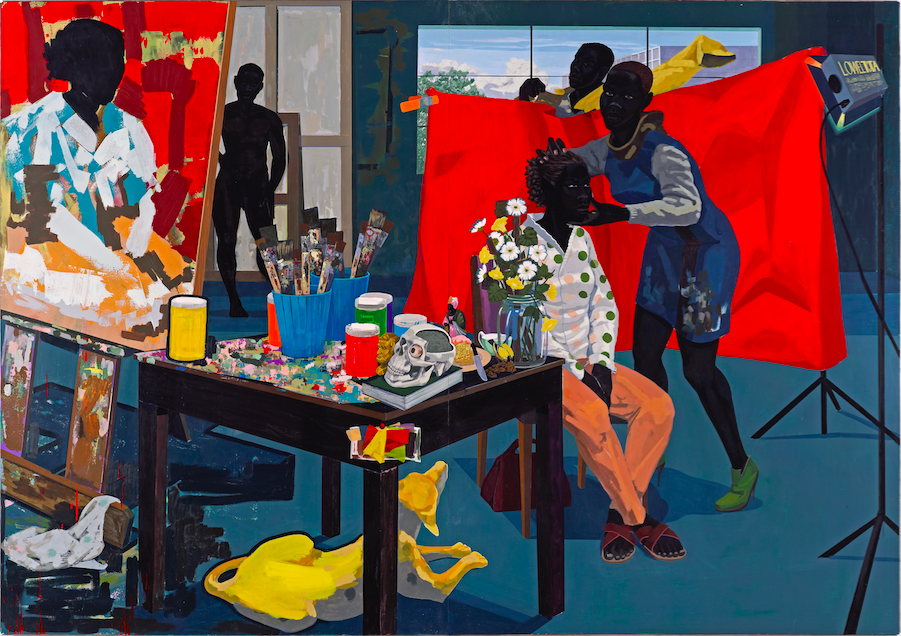

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Studio), 2014. Acrylic on PVC panels, 83 5/16 x 119 1/4 inches. ©Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

His paintings, then, are about the black cultural experience in the United States, but they also relate to the Western canon of art. A notable example is Untitled (Studio), 2014, a rendering of a painter’s studio. Four black figures activate the scene: a seated female model, two male models, and a female studio assistant or artist. This last figure stands poised in the center of the work, her hands adjusting her model’s head, her eyes meeting the viewer’s. In the foreground, beneath a work table, sits a languid yellow dog, looking up to observe the action. To the far left, the splashy color-blocked underpainting of the seated model rests against an easel, as a male nude stands in the background. His figure is solid and well-proportioned, suggesting he is comfortable in his nakedness. Is he waiting to be painted, or has he had his turn and is simply enjoying his state of undress? Nearby, another male figure dresses behind a red curtain, thrusting his arm into a mustard yellow shirtsleeve as his head tilts towards the viewer. With all the figures accounted for, the eye is drawn back to the table laden with the paraphernalia of the artist: buckets of well-used brushes, jars of paints, an anatomical skull, a vase of flowers, and snacks. Pinned to the corner of the table is a swatch of bold primary colors, the intensity of which helps unite the canvas. This painting is essentially about color, compelling the eye to move with pleasure over a series of vivid triangulations: the red connects to the drape and the jar of paint on the work table. The yellow shirt of the male figure draws the eye to the dog and a yellow container of paint. All these elements, and the motions of the figures, contribute to a sense of creative energy and purposefulness.

Taken as a whole, the composition alludes to other master paintings about the work of artists, such as Diego Velazquez’s Los Meninas, 1656, and Gustave Courbet’s The Artist’s Studio, A Real Allegory Summing Up Seven Years of My Artistic and Moral Life, 1854 -56. Marshall has studied the works of such time-honored painters, he tells us, “to know what they know and to do what they do at the highest level.”

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Painter), 2009. Acrylic on pvc, 44 5/8 x 43 1/8 x 3 7/8 in. ©Kerry James Marshall. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Marshall’s interest in commemorating the lives of black artists, and idealizing their creative work, is on vivid display in four other works included in the exhibition. In Untitled (Painter) (2009), Marshall gives us a “portrait of a painter painting a portrait of herself”, he has explained. Sitting in front of a paint-by-numbers self-portrait, a female artist wears a multi-colored striped blouse or painting smock. She sports an elaborate up-sweep hairdo and several hoop earrings in her right ear. Gazing directly at the viewer, she exudes a studied sense of style and confidence. In her left hand, she holds a palette abstractly covered with brilliant dabs of paint. In the background is her paint by numbers self-portrait which she has already begin to fill with paint A quick glance at the portrait and it is evident that she has taken artistic license over the image—making bold changes, abstracting the systematized scheme of this “anyone-can-do-it” artistic exercise.

It’s no accident that Marshall would include references to abstraction in his work. In an essay in the exhibition catalogue, Marshall addresses black artists’ relationship with abstraction. He comments that some black artists hoped that abstraction might “emancipate them and their artworks from racial readings.” Clearly, such “emancipation” is not part of Marshall’s agenda; he refuses to obfuscate or retreat from blackness. Rather, he synthesizes art conceptual narratives with black cultural histories and figuration in depictions of explicitly black life.

This paint-by-numbers image may have had another connotation for Marshall. In the fifties, paint-by-numbers books became something of a fad; many were found under Christmas trees across America. The decade also saw the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement in the South, where black people were starting to reimagine their lives. Marshall channels the determination and confidence of the movement in rendering a black female painter who, rather than lowering her gaze in submission, looks with her own agency beyond the frame, even as she exercises aesthetic freedom on the canvas behind her.

Self-satisfied black figures such as this are essential to Marshall's aesthetic project. His paintings cultivate racial pride and in so doing enrich and enlarge the story of Western painting, insisting on the inclusion of African-Americans animated with confidence and creative vitality.

Issue 1

Publication Date: May 17