American Vision

By Amy Benson

WE ARRIVED IN the dark, feeling brave and a little smug: yes, we will be the kind of people that drive seven hours and then get up and out well before dawn so we might have an Experience. And for some time we were on our own, the crowds we’d been warned about nowhere in sight. Alone except for an owl finishing its hunt and unseen songbirds waking for theirs. They could detect dawn a full thirty minutes before we could. The human body with its narrow band of light and sound and sensation, stumbling through the world with a sheaf of deeds and a crown on its head. We had come to let the artist work on us, eager to laugh at how easy we are to fool—fake parchment, paper crown.

We wound around a trail to the opening of the small rotunda set in the side of a hill, the woods having been cut well back to leave a clear shot at the sky. Inside the squat building was a round opening to the sky and soft, recessed lights at the juncture between wall and ceiling. The sky was dark and the room cold. We were glad we had remembered gloves. We stomped around the slate floor, until one of us tried the stone bench circling the wall. Heated! Heated! We stretched our bodies long on this luxury. We did not have to suffer for art. We were willing, but let this cup pass from us, and all that. We pressed ourselves against the warm stone and waited for something to happen to us.

And it did. We lost the sky. So gradually that we would not have been able to name the moment. The interior lights began to tinge pink against the matte white walls, bringing dawn inside. We thought this was it, a subtle light show that would have been undetectable by light of day. But then the light became fuller, bolder: Easter egg green turning by micro-shades to mustard yellow, Dreamhouse pink. By the time the dome shifted to a throat-catching fuchsia, the sky had turned into a piece of navy construction paper taped cleanly over the hole in the roof.

We blinked, squinted hard. Nope. Construction paper. If we had tried to project any melancholy or awe up at the stars we had spotted on the way in, they would have plunked softly back to the floor. No sky, no exit.

We ran for the door. Outside, a wild scene above—dawn and speedy clouds and birds swooping. We ran back in. Navy construction paper.

We kept this up. Out: busy, reassuringly unfathomable. In: gone. With a step-ladder, we could graffiti, We know what you’ve done, now give it back. But we loved not knowing, our eyes giving us every reason to doubt. Layered, starry dawn to flat circle filling our eyes. Back and forth. Then we stayed put, staring up. Structural aperture, eye aperture, one entry point to the brain stacked on another. At one point, a bird flew across and our brains told us that we were seeing a bird flying across a sheet of navy construction paper.

We lost the sky. We did this to ourselves. There was the sky, framed for us, but we gave ourselves over to the trick and we lost the sky. It’s okay. It’s part of the project of being alive: to see the frame and wander into the frame and forget the frame. To try some lenses on and forget we are wearing them. Where are my glasses? Oh, absurdity! They’re on my face. I was born with them. I can’t see without them. But sometimes you’re going to lose a sky.

Kim Dickey, Mille-Fleur (detail), 2011. Courtesy of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas.

This artist, James Turrell, specializes in the eye, rooting around in that wet sack for the mistakes it might make and then pass on, telling the brain there is no wall, no horizon, no sky. The artists of Light and Space—Turrell, Wheeler, Irwin. We had been tricked by Doug Wheeler, before, in what became known as the Infinity Room in New York. He turned all straight lines into curves, sloped the floor and ceiling, rounded the walls, painted it white and then lit the room with an even glow.

We’d been eager to be tricked then, as well. People lined up around the block to be tricked, queued in an anteroom until they were admitted in clumps of two or three to be tricked. We even knew the trick: You enter and lose depth perception, distance calculation; your eyes tell you there are no walls, that you may have entered ether and may not be walking on a floor. That you could walk, hands stretched before you, in any direction and not find the end. After a handful of minutes, you wonder if you might have accidentally wandered into an Afterlife. And if there may be no way out, no way back to the Life. And if the strangers you’ve been let in with are all that you get from here on out.

We are complicated beasts with minds we barely know. Turrell would like to make us happy to rediscover this again and again. We are! We are happy!

View of Town Branch Creek and south side of Crystal Bridges. Courtesy of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas.

We wandered the trails in the new light, pleased with ourselves. The paths followed a stream between mild escarpments and were dotted with sculpture, including a bronze pig named Stella, based on a once living pig, the plaque reads. She greets visitors, she is beloved. Her genial and eager expression, her shiny, unswollen teats. The non-living embodiment of the peaceable kingdom—look at how she loves her humans, and they her. How golden her brass remains, touched all over. Humans in their paper crowns, making sculpture of their food.

I would like to end there. Can I end there? Fold the paper over if you would like to end there. A good morning, an adventure.

We walked down the trails to town for coffee. The center of town was an actual square, and the approach to it undeniably quaint. Oddly, though, the traffic was unrelenting—slow and quiet, but without cessation. The stream of cars at 7 a.m. spoke to the fact that this town is Walmart headquarters, and headquarters to Walmart affiliates who saw the necessity, if not the pleasure, of moving to a small Arkansas town to be close to the mothership. It is home to the enormous art museum (the grounds of which we’d just left) because it is home to the gargantuan Walmart, the Walton family at the center of both. The town has swollen five-fold in the past eighteen years (increased by more than 12,000 just since the museum opened in 2011) with all of the square buildings and treeless suburbs that growth sweeps in. Mountains of drywall hoisted in concentric rings around the town center.

But in that center—the town square—it is still 1950. To the east the square is bordered by a Classical Revival courthouse, to the south, a southern goods outfitter, and to the north, a sleek coffee shop. The Walmart Museum fronts the full west block: red and white, old soda counter in the window, a Pleasantville five-and-dime. The trick here was that you had stepped back in time to the age of the general store as meeting ground, as balm—family owned, serving families. A lucrative mythology.

There’s another version of this counter in the National Civil Rights Museum, Memphis: sculptures of young black men and women sitting down to order in pressed shirts and dresses. A video plays overhead, footage of a sit-in wherein these self-contained women and men are yelled at with spitting rage by white men in shirtsleeves. In an artist’s interpretation, perhaps, the men’s heads might be represented by buzz saws, closing the gap between word and meaning. But art is not needed here; the distance collapses in the actual video: one arm reaches out and pushes, one arm reaches up to protect its head. Once thresholds are broken, rage becomes flesh and walks among us.

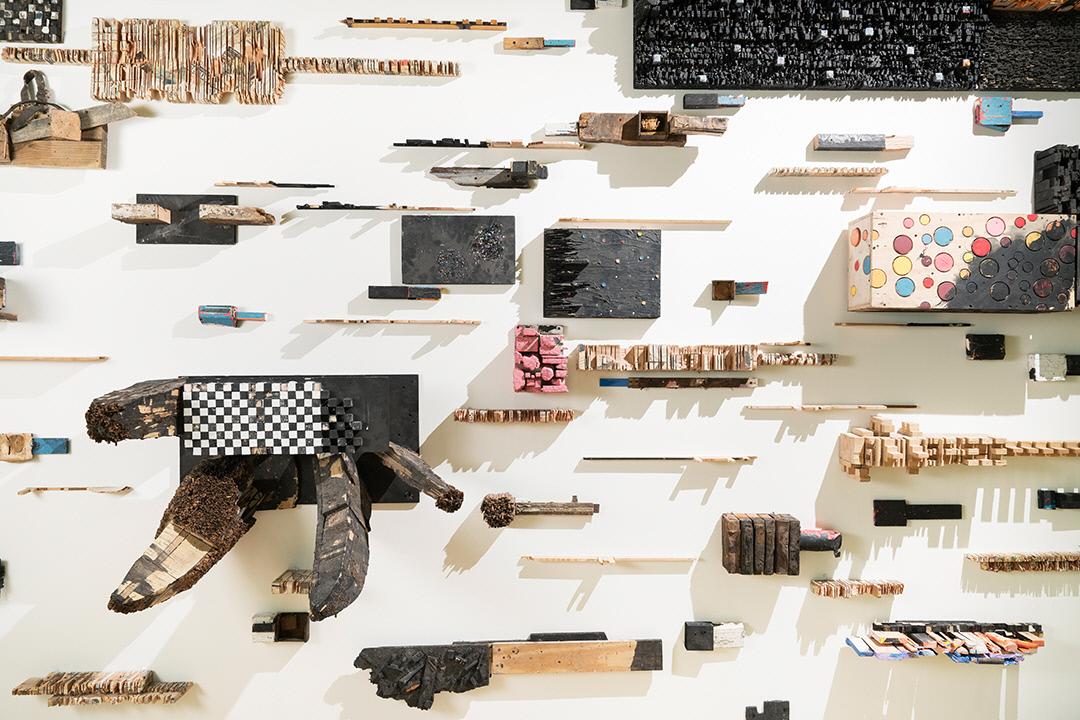

Leonard Drew, Number 184T (detail), 2017. Courtesy of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas.

But the trick! The trick was that we had not crossed a threshold, and happy commerce was the order of the day—five cent, ten cent! Clink, clink! The storefront was both history and unmolested by history. Save up your sweat-earned wages and drink a Coke with dignity in your suspenders. As upright as the obelisk in the town center we’d caught only through the corner of our eyes. When we turned our heads, we took in CONFEDERATE at the base of it and a soldier with a gun at the top. The square was calm in the early morning light, rush hour gliding slowly past.

What we felt was white person horror and fear; we cannot know what it is like to be a black person who travels to see some art, seeks out coffee, and turns the corner onto this homage to better, simpler times. Times when said person might be killed, with impunity before cheering crowds.

We averted our eyes—those receptors for a narrow band of visible light—until we were swept into the chrome coffee shop, slid down its notable tilework toward hot drinks and lemon bars. We were contemporary consumers once again, dread evaporating.

Until we exited and saw that the monument had not blinked away, and, moreover, that it had plaques we felt obligated to read, as we’d read the plaque for Turrell’s The Way of Color just an hour before. But a monument like that towers, in this case twenty feet above you, and forces you into the semblance of reverence if you draw near.

On one side:

They Fought for Home and Fatherland.

On another:

Their Names are Borne on Honors Shield.

Their Record is with God.

And another:

To the Southern Soldiers

Erected by A. J. Bates And

The James H. Berry Chapter

United Daughters of the Confederacy 1906

On all sides:

CONFEDERATE CONFEDERATE

CONFEDERATE CONFEDERATE

This was a linguistic trick, renaming chattel slavery and manifest destiny and patriarchy and treason, “Home,” “Fatherland,” “Daughters,” and “Honor.” And a perceptual trick: it is normal to center your town around a military monument. But it is, in fact, highly abnormal to erect a monument to the losing side of a war, to an army that mustered to retain chattel slavery. That was the lie right on the surface of the stone, but there were others, I found later. At 718 Confederate monuments, the US has hundreds more to the losing side of a war than any other country. More, even, than to any winning side of a civil war. More than winning juntas and dictators and fascist regimes. The memorial did not name any soldiers, as Stella had been named one mile to the north, that real (doomed) pig. Historian Rebecca Howard says that is because the demand for Confederate monuments during the rise of Jim Crow was so great that they were mass-produced, plunking generic soldier forms on top of obelisks in thirty-one states. Mass-produced Americana decades before the rise of Walmart. By 1906, this Ozark town had been demographically overhauled by white migrants from plantation landscapes like Alabama, Mississippi, and southern Arkansas. The Ozarks had precluded dependency on large-scale enslaved labor; it had been home to fervent Unionists before the war, and then home to Union-established colonies of Arkansas refugees fleeing the conflict.

I worry that the art has drained from these sentences. Art takes—Turrell took—our eyes and fills them with color and depth and thoughts that are somehow there and not quite there, lets us live in thrilling and generous confabulations. And yet there is this: The Daughters of the Confederacy moved to this town after the Confederacy and yet they have claimed its center as their own for the past 113 years.

The art, the trick, of this statue is that it pretends to commemorate history, when it actually replaces it. Failures internal and external to our eyes.

Leonard Drew, Number 184T (detail), 2017. Courtesy of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas.

But we don’t call perceptual tricks failure when we look at art. We call it wonder. Transformation. Transportation. We are happy when we feel we have been altered. When we find ourselves a few steps removed from the raw materials of life. Messing with our senses and entering into wonder feels like the necessary lever out of the tar pit into which we will inevitably sink—just not right now. Not yet.

We were happy later that day and the next, as we walked through the museum’s conundrums. Crystal Bridges is the ambition of the youngest Walton heiress, a destination museum of American art, built into a valley dotted with sculpture and blooming dogwoods.

The museum structure is formed by linked metal carapaces and looks like the lair of benign geniuses, a twenty-first century version of Olympus, low among the pools, between the hills, rather than exalted columns in the sky. A museum created through billions in retail and low-wage, underemployed, uninsured labor profits. Built on the wreckage of local economies and small businesses, on invisible-to-us Chinese industrial poisoning. On the proliferation of disposable culture. Through Arkansas tax exemptions and infrastructure manipulation. With nationalistic pride.

We stuffed our eyes full. Greedy, a little delirious.

Within the museum, art by Howardena Pindell, by Maya Lin, by Angela Drakeford and Michael Waugh and Elizabeth Alexander. All thinking through history by making things that bristle and jut and drip and shine. The parts of America that have not often been included in the high-art circuit, that haven’t often been included in “America,” have been given pride of place in the glass wing that spans the damned Crystal Spring. In Ruth Asawa’s wire sculpture, her history of US internment during World War II is wrapped so tight it threatens to spring. Around the corner, Leonardo Drew’s fury/fear/decay fills a long wall with its impossible combination of catalogue and explosion of American ruin. Blackened wood is asked for one last labor, organizing itself as library of salvage on one end, swirling into a monster storm on the other.

Outside the walls, a giant, pregnant spider by everyone’s favorite no-longer-neglected artist, Louise Bourgeois; Kim Dickey’s lush glazed terracotta wall—unsettling because it looks so much like a medieval tapestry that is itself trying to look like Nature; Robert Tannen’s sly brushed metal letters spelling “Art” screwed into rocks throughout the grounds; and a glorious bare-silver tree-in-wind by Roxy Paine. It was like a treasure hunt in a national park, finding these many witty, generative ways of being a creature in nature who also frames Nature. Literally, in the case of the empty gilt frame hanging along a trail.

Ruth Asawa, Untitled, 1965-1970. Courtesy of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas.

Further along this trail, we spent time with a piece that, in a rocky landscape, we only slowly realized was art. Plain stone plinths of varying sizes, wound in a serpentine trail down to the brook and rose up the other bank. We were reminded of graves and of Stonehenge, which has become the stand-in for important but unfathomable ancient culture. A Place Where They Cried, the piece is called, translated from the Cherokee, Nunna daul Tsuny. It was meant, the plaque said, to pay homage to the forced expulsion of the Indian nations from the United States into the US territories. We didn’t know, we hadn’t considered that Bentonville was along the route of the Trail of Tears, the Oklahoma interments only another fifty miles west. And we had read the plinths wrong: they were winding up from the brook, having crossed it, heading west. It would have been March, the brook high with snow melt from the notably harsh winter. Their feet would have likely been bare, at least that was how many began the march. Also with diseases that barred them from entry to towns along the way, forcing longer routes. The stone was adept at evoking eternal personhood. The suffering of the living and of those who didn’t make it through the water. One contingent led into an Arkansas swamp from which they never emerged, others dying on the eastern banks of the Ohio and Mississippi, waiting days for ferrymen who would charge ten times the going rate. The stone did not evoke the daily ration of one cup of water, one cup of boiled corn, and one turnip, but that is not the fault of the stone.

We didn’t take any pictures there. It wasn’t an adventure or an attraction. We wanted to pretend that we knew things we didn’t, had the capacity to feel things in our catacomb chests. What we knew to feel, instead, was that we were intruding, as if the site required a form or a ritual we didn’t know and should not have known.

Later, we visited The Museum of Native American History in town, housed in what looked like a 1980s church and containing beautifully displayed and researched remnants of some Native cultures in the Americas: displays of arrowheads, pottery, and pipes all tastefully lit behind glass. We wandered with explanatory wands tilted to our ears.

Outside, the curators had placed a large teepee upon a spread of dolomite rocks. A sign invites visitors to search for arrowheads, one free per child, fifty cents for each additional. Of course we searched. How could we resist this national pastime: turn over a rock, a bit of dirt, and hope to get blessed with a remnant of an extinguished culture. I think that is the feeling for most upon finding an artifact or claiming a distant lineage: lucky or chosen, somehow imbued with a touch of the nobility retroactively blanketing Native history.

Of course we dug through the rocks, looking for flint work. We found them, and found, when we asked, that they had been “hand flinted” and dyed in India. Actually in India, Columbus’s original destination. Where the wages are—well, who knows what the wages are? The museum does not pay indigenous Americans a living wage to carry on traditional practices. Free arrowhead if you can find it.

Our son found four; we paid for the extra and he treasured them until he treasured something else.

This was a trick, but so was the reverence of the glass cases and hushed lighting. Items disinterred from burial mounds and extracted from “motivated” sellers. The displays were otherwise respectful and admiring, aiming to impress upon visitors the skill and ingenuity of people routinely dehumanized. But the trick was the lack of blood. The sanctity of the object hid the humans, their removal, and the acquisition of their possessions. The town square gave pride of place to several tons of ginned up history. The museum was the mirror opposite: fragments of retrieved history with no place. With no sense of the Trail of Tears running somewhere under the industrial carpet and floor joists, under the dolomite quarried a thousand miles from here.

Elizabeth Alexander, Sommerfarm, 2014. Courtesy of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas.

Lone Dog’s Winter Count, the last display in the museum, held a whole world, though. It was meant to. It is a buffalo skin from the 1800s, onto which pictographs were dyed as a tribal record. Elders chose one event each year to commit to the skin, then the keeper of the skin designed a symbol, creating a spiral of history, of story, widening from the center. Hundreds of notable events in a year must have fallen into the ether of individual memory, while only one found a pictorial form. The tribe curated this selective memory with a vision for their future selves gathered around a widening spiral, unfurled. The skin holds art and story and history and future, imperfectly, all in one. But they did not, perhaps, anticipate cataclysmic discontinuity—that the meaning of the pictographs would now often be guessed at.

The Winter Count made us wear our experience with A Place Where They Cried even more uneasily. Aestheticizing history is not the same thing as falsifying it. I don’t mean to equate art’s manipulation of materials and viewer with a Confederate statue or a dyed arrowhead from India. But our experience at the side of the brook depended upon the eradication of perceived threat. Crystal Bridges was built, in part, to wed art and nature, and it does. But nature, in this vision of America (for that is what the museum offers, a vision of America), is a place of joy and transformation and contemplation. This rejuvenating nature is possible because European Americans killed or subjugated every threat to human life and dominion (except weather, viruses, and the by-products of human culture, which are now ascendant). In a valley clear of actual Native Americans a mournful, moving sculpture evoking the Trail of Tears could be installed. Dark stone plinths hitting our myth-and-history neural clusters, lighting them up. We’d gotten up before dawn to have our eyes messed with and not once did fear flicker through them.

Kim Dickey, Mille-Fleur (detail), 2011. Courtesy of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas.

We had booked, for the trip, a room in a peculiar mansion. We should not have been surprised to find the host equally peculiar. The surrounding hills have a powerful energy, he said—the water is full of healing quartz and radium. Our child was special, he said; he would pay for his college tuition when he was old enough. Did we know that it was not warming on the way but a global ice age? He was readying a hydroponic greenhouse. We must see beyond the story in the news, he said. We must be willing to lose the sky. Or is it: we must be willing to know that the sky is still there?

We escaped his alternative reality as quickly as we could, back to the picture frame hanging in the woods, to the giant silver tree blowing in an absent wind, to the navy construction paper sky.

On our final day, this strange proprietor informed us that a bachelor party would be occupying the other rooms that night and that the last such party had ended at dawn, with dancers and vats of liquor and bottles smashed throughout the house. We fled for good. Feeling reckless, we registered at our first boutique hotel, one of a small chain of “art hotels” that locate themselves adjacent to destination art museums. Its entire first floor was a contemporary art gallery (“Labor” was the theme of the current show—socially conscious works for the high-art consumer), but art was tucked everywhere. The “Please Clean My Room” door-handle notice?—a painting of a child in a gas mask by Vee Speers. The save-the-earth please-don’t-wash-our-towels notice?—a fantastical photograph of flapping laundry six lines high by Glenda Leon.

We had not known about boutique hotels, may never stay in one again. But for that night we were living in a thrilling concept—we were a thrilling concept, wry, glossy, and lovingly curated. We became the kind of people who were met with installations of ceramic AstroTurf when the elevator doors opened, who showered under rain faucet heads three floors above the intricate, unsettling dollhouse-like dioramas of Karine Giboulo depicting Chinese factory life, and the migrant worker text/image collages of Lina Puerta. The kind of people whose child carried a (recycled) plastic penguin (created by a trans-Euro art collective) nearly his size to our room, because that was the freedom we had accessed. Pay the price of admission (better yet, have someone else pay it) and art is yours—touch it! take it to your room! It is delicious to be such people. Literally. The chocolates on the pillows were Vosges—as salty and caramely as contemporary tastes require.

Amy Benson is the author of Seven Years to Zero: Sketches of Art in the Anthropocene (Dzanc Books), winner of the Dzanc Books Nonfiction Prize, and The Sparkling-Eyed Boy (Houghton Mifflin 2004), winner of the Bakeless Prize in nonfiction, sponsored by Bread Loaf Writers Conference. Recent work has appeared in journals such as Agni, BOMB, Boston Review, Denver Quarterly, Gettysburg Review, Kenyon Review, PANK, and Triquarterly. She teaches writing at Rhodes College in Memphis.